In the aftermath of Swami Vivekananda’s 1893 speech at the World Parliament, the floodgates from the East opened. Although Vivekananda himself was ostracized by orthodox monastic orders for crossing the forbidden “kala pani” (black waters), his journey to America and the high-profile press coverage he received inspired ambitious spiritual leaders who were keen on taking Hindu thought to the West.

Newspapers during this period are replete with ads for various mystics, swamis, and holy men delivering lectures across America and offering sundry spiritual services. And they weren’t all of Indian origin, either. Travelers from across Europe wound up in America, claiming to have learned the mystical secrets of the hindoo in India. Here’s a sample:

The report below was published in the San Francisco Call in 1900, announcing the arrival of one Swami Ram to America:

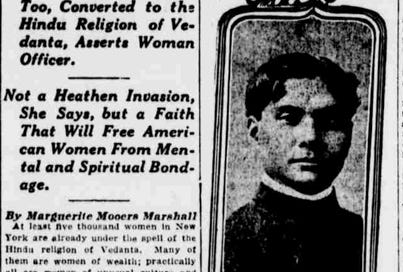

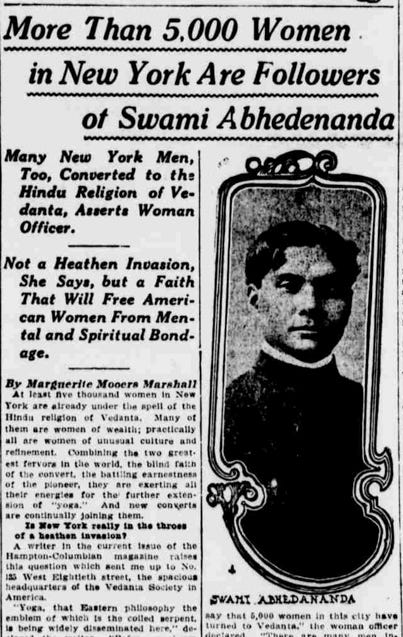

During this period the Vedanta Society also continued to grow, particularly in New York under the stewardship of Swami Abhedananda. The Vedanta Society found particular appeal among the women of the New York elite, which caused no shortage of consternation among the religious establishment (a topic for another time):

From the Evening World, 1911:

And here’s a report published in the Evening Star in 1905, announcing the arrival of one P. Ramanathan from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), warning that he had arrived to “convert Americans to Hindooism”:

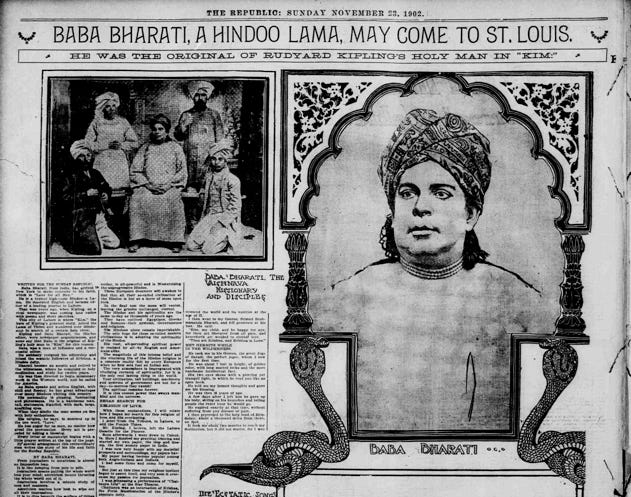

Of all the individuals who arrived in America in the wake of Swami Vivekananda’s speech, one of the most influential and enigmatic figures was Baba Bharati.

Born in Dhaka in 1858, Bharati (whose birth name was Surendranath Mukherjee) came from a “quintessentially colonial Bengali bhadralok household"(Carney 77). Both his father and his uncle served in administrative roles in the Raj— a deputy magistrate and a judge on the Calcutta High Court, respectively. Bharati would go on to study journalism at the University of Calcutta (Carney 77). As a reporter for the Lahore Tribune in the early the 1880s, Bharati came to know Rudyard Kipling, who was then also working in Lahore for a rival newspaper. Bharati himself recounted this period of his life in an article written for the St. Louis Republic in 1902:

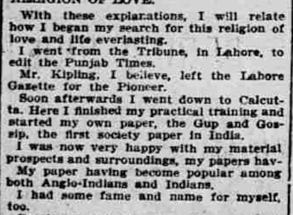

Bharati states: “I went from the Tribune, in Lahore, to edit the Punjab Times. Mr. Kipling, I believe, left the Lahore Gazette for the Pioneer. Soon afterwards I went down to Calcutta. Here I finished my practical training the started my own paper, the Gup and Gossip, the first society paper in India.”

During this stage, Bharati became increasingly preoccupied with spiritual affairs. Bharati recalls how while witnessing a Chaitanya Lila (a staged production depicting episodes from Krishna’s life) in Calcutta, he was overcome with religious feeling and decided to leave his journalism career behind.

In 1890, Bharati would travel to Varanasi and be initiated into sannyāsa (ascetic renunciation) by Brahmananda Bharati. And although his guru was not a Vaiṣṇavite himself, like many other spiritually minded Bengalis during this period, Bharati was drawn into the broader Vaiṣṇavite revival that inspired a wide range figures including the political firebrand Bipin Chandra Pal and Rabindranath Tagore. In 1891, Bharati was invited into the Hari Sabha, an influential group of Vaiṣṇavites where he would develop a close relationship with the leader of the group, Ananda Charan Datta. It was Datta who would first give Bharati the mission of spreading Vaiṣṇavite thought on American shores (Carney 79).

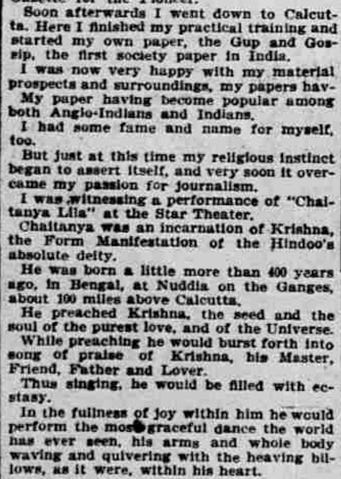

Bharati would do just that in 1902, when he arrived in New York. Bharati arrived in America with neither a plan nor a group of eager disciples waiting for him at the port. Fortunately, his arrival did garner prominent press coverage. A cover story published in the New York Herald in 1902 (reprinted in the St. Louis Republic and shared above) introduced Bharati to a wider audience and even garnered the attention of Indophiles such as Edmund Russell. Russell warrants a post of his own, but he was an actor and producer who would often throw “oriental-themed” soirees at his Indian-themed home in Washington, DC:

Bharati quickly became a fixture among New York’s spiritual vanguard, and began regularly hosting lectures and discussions on Hindu spirituality and Krishna devotion. This period of Bharati’s life would culminate in 1904 with the publication of his book, Sree Krishna— The Lord of Love.

Aside from further raising Bharati’s profile in America, the publication of the book would have far-reaching effects on India’s nascent independence movement. As recounted by Gerald Carney, Tolstoy would end up translating passages of Sree Krishna into Russian, and also ended up incorporating excerpts of the text into his famous Letter to a Hindoo, a rebuttal to Taraknath Das’s request that Tolstoy support a violent overthrow of the British Raj. Gandhi— who was then working as a barrister in South Africa— was deeply impacted by Tolstoy’s letter, and would seek to circulate its message widely (Carney 88).

Following a brief sojourn in Boston, Bharati would then venture west to Los Angeles, the city that would become his headquarters in America. Bharati continued to deliver lectures and eventually attracted a dedicated group of disciples. During this period, the Los Angeles Herald is replete with ads like the one below, published in 1905:

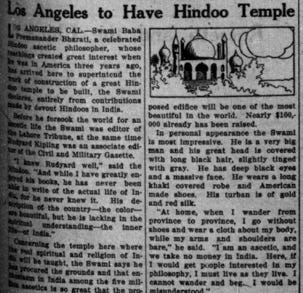

In 1911, Bharati would go on to establish a Krishna temple in Los Angeles, the city’s first.

Bharati’s contributions to the propagation of Hindu spirituality in America are well-documented, but less attention is paid to his work in disputing well-established stereotypes regarding the hindoo in American broadsheets. From the very beginning, Bharati’s journalistic sensibilities inflected his spiritual mission. In the report below about his Krishna temple in LA, Bharati criticizes Kipling’s India, as depicted in his immensely popular novel, Kim.

Bharati states: “I know Rudyard well… And while I have greatly enjoyed his books, he has never been able to write of the actual life of India, for he never knew it. His description of the country— the color— was beautiful, but he is lacking in the spiritual understanding— the inner life— of India.” Indeed, in addition to his book on Krishna, Bharati would also publish a serialized novel titled Jim, an Anglo-Indian romance founded on real facts,” written to “counter the misinformation of Kipling’s Kim” (Carney 86).

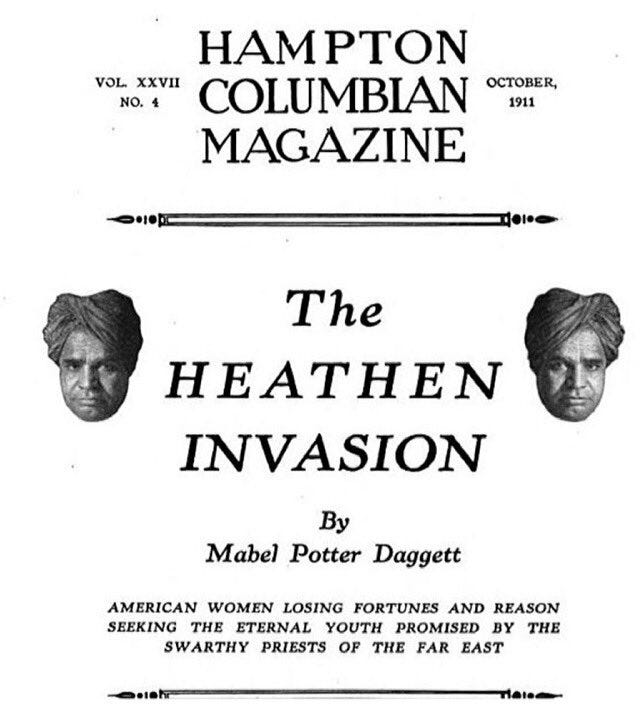

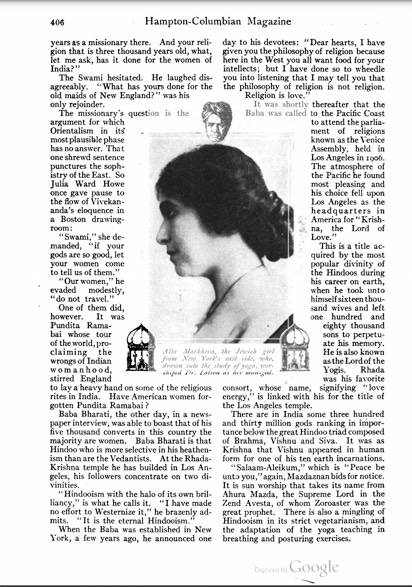

Bharati’s public profile made him an easy target for critics. He would feature prominently in Mabel Potter Daggett’s infamous essay, The Heathen Invasion of America, published in 1911:

Bharati, Daggett writes, “was able to boast that of his five thousand converts in this country the majority are women.” “Baba Bharati,” she continues, “is that Hindoo who is more selective in his heathenism than are the Vedantists.”Daggett then describes how Bharati turned Los Angeles into the headquarters for Krishna worship in America, whom she describes as “the most popular divinity of the Hindoos… when he took unto himself sixteen thousand wives and left one hundred and eighty thousand sons to perpetuate his memory.”

In a subsequent passage (shared below), Daggett notes that Bharati’s book on Krishna contains a dedication to his guru as evidence that “a guru’s bidding is obeyed even when he tells a disciple that the highest spiritual attainment in yoga will require the renouncement of home and family ties.”

For followers of #HindooHistory, the material above will not come as a surprise. Much of the hysteria around pernicious hindoo influence during this period is fixated on the alleged susceptibility of women to the wiles of the “swarthy priests of the Far East.” The hysteria is amplified in Bharati’s case given his connection with Krishna, whose association with the gopis (or milk maids) was often characterized by American commentators as licentious.

Bharati was by no means the only figure who was a target for criticism. What distinguished him from other spiritual figures in America at the time, however, was his vigorous rebuttal of criticism in the press. Bharati’s journalistic background provided him with the tools necessary to dispute claims that had been circulating virtually without interruption from the early 19th century onwards.

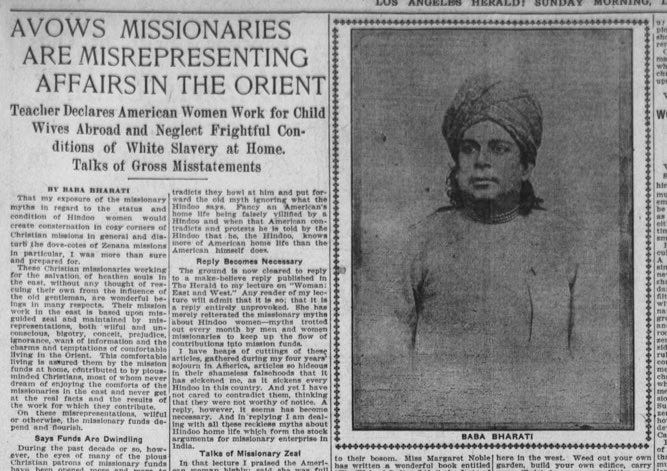

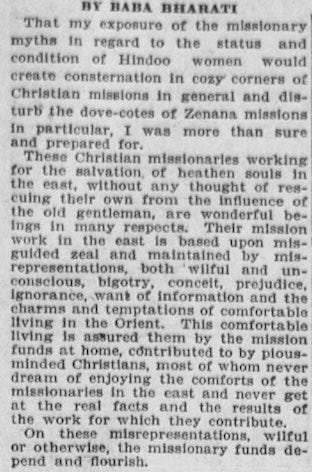

In a 1906 article published in the Los Angeles Herald, Bharati takes missionaries to task, insisting that they are deliberately misrepresenting conditions in India.

In a blistering attack, Bharati asserts that “mission work in the east is based upon misguided zeal and maintained by misrepresentations, both wilful and unconscious, bigotry, conceit, prejudice, ignorance, want of information and the charms and temptations of comfortable living in the Orient.” Bharati then asserts that funding for missionary funds are dependent on these misrepresentations, since they often serve to elicit donations from “pious minded Christians” in America.

Bharati then links missionary representations to the increased awareness of Hindu spirituality among Americans. On Bharati’s account, increased exposure to first-hand accounts of Hindu spirituality led to increased desperation among missionaries, as they found “impressions of one myth after another about the Hindoo’s inner life which they have so long traded upon being wiped out from most American minds.” This represented a significant shift in the representation of the hindoo in American culture, as such misrepresentations were “long unchallenged by the Hindoos here or out in their own country.”

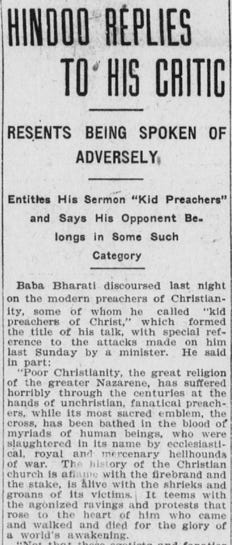

Bharati’s aggressive rebuttal won him fans and detractors; he continued to give lectures and win ardent followers both in Los Angeles and Boston, but was also the target of attacks from preachers. The following year in 1907, we see another article in the Los Angeles Herald, in which Bharati excoriates his critics, arguing that they were not only misrepresenting Hinduism, but also doing a disservice to their own religion:

Calling his critics “kid preachers,” Bharati turns a common criticism of Hinduism as a violent, bloody religion on its head, accusing his critics of turning the peaceful religion of Jesus into a tool for colonial domination and war. Bharati laments that “poor Christianity, the great religion of the greater Nazarene, has suffered horribly through the centuries at the hands of unchristian, fanatical preachers, while its most sacred emblem, the cross, has been bathed in the blood of myriads of human beings who were slaughtered in its name by ecclesiastical, royal and mercenary hellhounds of war. The history of the Christian church is aflame with the firebrand and the stake, is alive with the shrieks and groans of its victims."

With regard to their treatment of Hinduism, Bharati accuses his critics of harboring an attitude “of supreme contempt.” “To them,” Bharati continues, “they are pagan religions, and as such could contain nothing worthy of their attention or examination.”

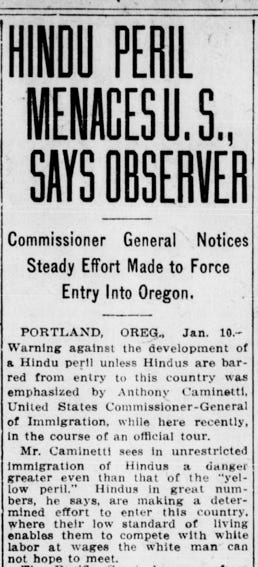

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bharati did not confine himself to spiritual matters, either. In the early 20th century, immigration from India to the west coast of America in particular was a matter of great concern domestically. Newspapers warned of the “Hindu Peril” threatening America.

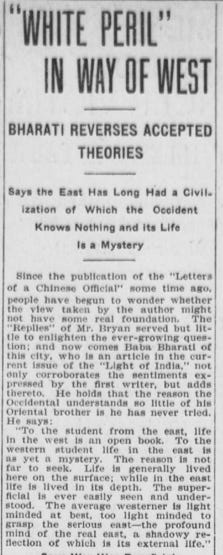

Amidst this furor, Bharati published an essay titled the White Peril, deftly turning American paranoia about Indian immigrants into an anti-colonial manifesto. Originally published in the Light of India, Bharati’s essay would garner responses reproduced in papers across the country.

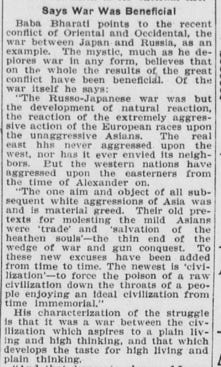

In addition to accusing the “Occidental” of lacking understanding of the Orient, Bharati also praises Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, which he characterizes as “the reaction of the extremely aggressive action of the European races upon the unaggressive Asians.” Bharati then characterizes India— “the cradle of religion and refinement and learning”— as “now the poorest and most miserable, all on account of the white peril.” Bharati continues: “Political death, industrial destruction, commercial stagnation, social degradation and spiritual demoralization are the earmarks of British predominance in that unfortunate country.”

In characteristic Baba Bharati fashion, he made it clear that Indians were not the only victims of “western civilization,” which had, according to Bharati, “raised selfishness to a religious creed, mammon to the throne of God…deified sensuality, glorified materialism, beatified sin.” “In the language of the Vedas,” Bharati writes, “civilization is maya— the magic illusion of woman and gold.”

His health failing, Bharati left America for India in 1911, and would pass away two years later in 1913. Although he is predominantly known as a pioneer of Krishna worship in the west, his work as a pugilistic writer deserves greater notoriety. Bharati’s multi-faceted approach also reflects his understanding that the representation of the hindoo in America could not be separated from India’s colonial subjugation. Bharati astutely observed that missionaries were responding to economic incentives, and that the misrepresentations that had been freely reproduced in American newspapers were specifically tailored to elicit donations from the church-going public. And in The White Peril, Bharati states that "the one aim and object of all subsequent white aggressions of Asia was and is material greed. Their old pretexts for molesting the mild asians were ‘trade’ and ‘salvation of the heathen souls’— the thin end of the wedge of war and gun conquest.”

In melding his spiritual work with a broader anti-colonial outlook, Baba Bharati emerges as a key figure in the #HindooHistory pantheon. As Hinduism arrived in America and found adherents through the Vedanta Society and other spiritual organizations, Buchanan’s representation of the hindoo continued to lurk in the background, persuading Americans to be wary of smooth-talking Swamis whose high-minded talk of religious unity was apparently just a lure to draw gullible American women into the depths of heathenism. Bharati understood that these two stories were intertwined, and that to propagate Hindu spirituality on American shores, it was necessary to strike at the heart of the misrepresentations that had embedded themselves in American popular culture over the century preceding Swami Vivekananda’s arrival. From a methodological standpoint, this makes Bharati’s contribution all the more valuable, as he provides a roadmap to understanding how disputation over the representation of the hindoo would continue to be be deeply embedded in contemporary political and social developments in the years to come.

***************

Carney, Gerald. Baba Premanand Bharati: His Trajectory into and through Bengal Vaisnavism and the West in The Legacy of Vaiṣṇavism in Colonial Bengal (Routledge Hindu Studies Series) (p. 87). Taylor and Francis.

The name of the Leader of the group was not Ananda Charan Das but "Radharaman Charan Das", his bio is in the book LIFE OF LOVE by Dr. Kapoor. Thanks for the note 🙏