Philip Deslippe is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, finishing a dissertation on the early history of yoga in the United States from the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century.

His research on Asian, metaphysical, and marginal religions in modern America has been presented in eleven countries and translated into nine languages. He has published a dozen articles and chapters for academic journals and edited volumes, written over two dozen articles for popular audiences, and co-authored several investigative news features. In 2011, he introduced and edited a new and definitive edition of the metaphysical classic The Kybalion for Tarcher/Penguin.

Recently, Philip served as a historical and archival consultant and an on-camera subject matter expert on Kundalini Yoga and the Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization (3HO) for the 2024 docuseries Breath of Fire on HBO Max, and is the co-creator and co-host of Temple of Steal, an unofficial companion podcast to Breath of Fire on Axis Mundi Media with Stacie Stukin.

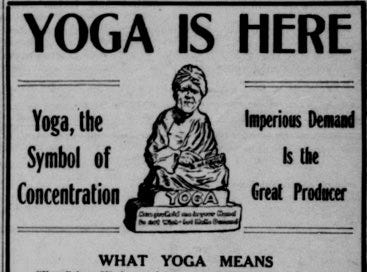

HH: Thanks for doing this Philip! I've been following your work for a couple of years now and I'm really looking forward to this conversation. Yoga features prominently in the newspaper in the early-mid 20th century, but as you know the term is used in a wide range of contexts that makes clear definition difficult; "yoga" is variously used to refer to magical powers wielded against innocent American women by nefarious Hindoo mystics, innocuous Indian fitness routines that aid relaxation, and even a figurine that you can put on your desk to manifest business success! Your work has been of great assistance to me as I've tried to untangle this complex of representations, and I especially appreciate your deep dives on the individual characters we see emerge during this period. Before we get into the meat of the topic, however, I was hoping you can tell us about how you got interested in this topic in the first place. What is it about yoga that captured your imagination?

PD: Thank you. I initially started researching what I call “early American yoga,” yoga in the United States from the late-19th to mid-20th centuries, when I was researching someone named William Walker Atkinson (1862-1932). Atkinson was an incredibly influential and prolific writer who authored books and magazine articles under more than a dozen pseudonyms. One of these was “Yogi Ramacharaka.” As I started to look into the yoga within the Yogi Ramacharaka works, I saw something that was very different from the flowing sequences of postures that is currently understood as yoga.

I was intrigued, and I started to intently (maybe obsessively) look for information on what was taught as yoga during that time, roughly the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century. That led me to conduct research in dozens of archives across several continents and pour over digitized historical sources. Right now, I’ve coded out data from about 7,000 lectures and classes and have compiled biographical data on about 100 different figures.

The most obvious thing that captured my imagination was how different yoga during that time was, but later, I was interested in the lives of the figures who taught yoga then: who they were, how they came into the profession, and what became of them. As a historical project, it has a bit of a “Goldilocks” feel to it. It is challenging, but not impossible, to uncover facts and documents about these figures, and so there is a consistent and satisfying reward in solving the next mystery or finding the next piece of the puzzle. I’ve been able to connect with the descendants of many of these early yoga teachers, and being able to share discoveries with them has also been both rewarding and a source of encouragement to keep going.

HH: I really appreciate your focus on the individual characters who emerged during this period, and not just because many of their stories are incredibly entertaining. The sheer number and diversity of the early “Hindoo” magicians, mystics, and yogis who traveled across America is remarkable. Along those lines, I was hoping you could give us some historical and cultural context here: How did a figure like “William Walker Atkinson” emerge in the first place? Here I am thinking of your article titled “The Hindu in Hoodoo: Fake Yogis, Pseudo-Swamis, and the Manufacture of African American Folk Magic”, where you trace the emergence of the Yogi in America alongside the Hindoo swami as a “Hypnotic Wonder-Worker.”

PD: The “Hindoo” figures we see in the United States during nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries are coming out of the many ideas that Americans have about India during this time as being a fantastic place of magic, mystery, poverty, unusual religion, etc. Mike Altman discusses a lot of this in his work. Some of these ideas circulate in popular culture. Before the American Revolution, merchants are going back to forth from India bringing goods, souvenirs, and stories back with them. Missionaries are going to India and relaying accounts to their congregations and supporters. India shows up in children’s textbooks. Ideas about India show up in the persona of stage magicians and fortune tellers, and they appear in newspaper article, pulp magazines, and dime novels. And as I’ve recently written about, India shows up in common speech, maybe most noticeably in the word “fakir” which becomes the default way to refer to sidewalk peddlers after the Civil War.

There’s also metaphysical spirituality. Pat Deveny, from the International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals, wrote an insightful chapter on what he called an “amalgam” in the late-19th century in which all of these different spiritual schools of thought begin to overlap and merge: Spiritualism, occultism, positive thinking and New Thought, and important here to note, the Theosophical Society and Asian religions, or at least what Americans thought of as Asian religions. So, if you’re involved in any strand of metaphysical spirituality in the late-19th century onward, to some extent you are going to be looking towards what Catherine Albanese called "Metaphysical Asia” as a source of wisdom.

Two things are important: there is no clear line between ideas about India in popular culture and those in the metaphysical world, and these ideas are very much in circulation. The idea, for example, that Hindu yogis and swamis held hypnotic mental powers is held by serious metaphysical seekers as well as authors writing pulp fiction or popular silent movies. So, the travelling yogis and swamis that I study are able to draw in Theosophists and Spiritualists as well as ordinary people from any random city in the country. Americans may have had bizarre, fantastic, and incorrect ideas about India, but those ideas are still there, and we need to take them seriously if we want to understand how India and people from India are viewed during this period.

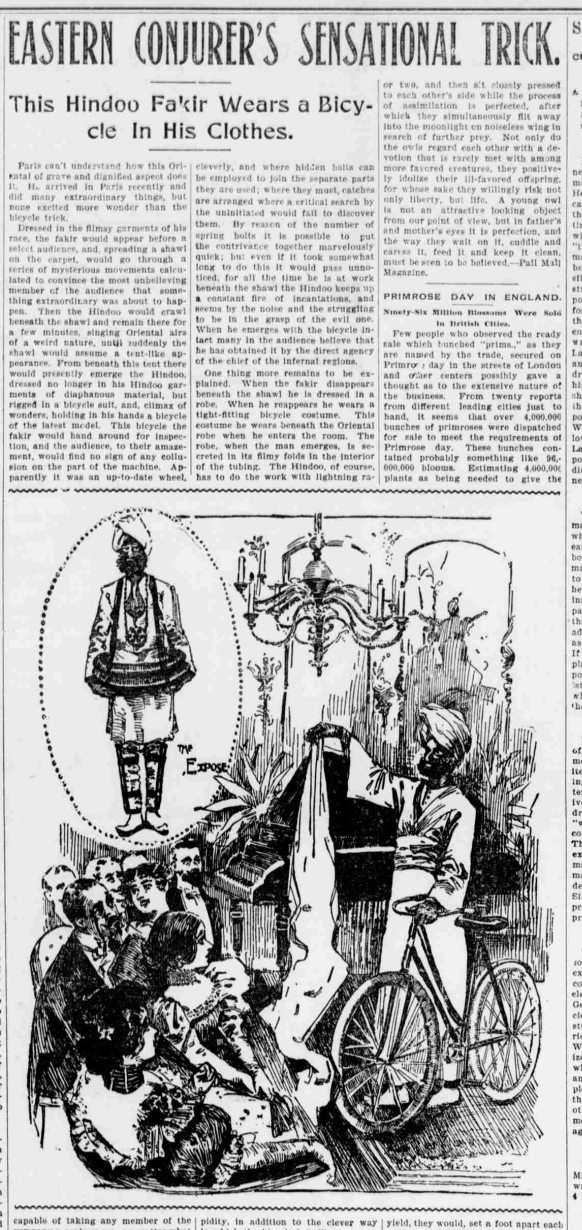

HH: I think the last sentence of your response is absolutely critical, and makes a great segue into a topic you’ve written about extensively. In a recent paper titled “Doctorji the Divorce” you delve into the story of Bhagat Singh Thind, whose name readers of #HindooHistory will likely recognize in the context of fight for American citizenship. As a brief background, Thind claimed that as a high-caste north Indian, he was “Aryan” and therefore should be considered white for the purposes of naturalization. The plea was rejected by the Supreme Court in a landmark case in 1923. What most readers won’t know, however, is that after the Supreme Court decision, Thind—like dozens of other Indian immigrants who had been granted American citizenship—was essentially left stateless and would go on to become a metaphysical lecturer who along with his American wife “conducted healing services in the late mornings and early afternoons and lectured twice a day on topics that were both of a general spiritual nature and pointed directly to India such as Vedanta, reincarnation, and ‘The Sacred Syllable OM-AUM.’” And he wasn’t the only one.

You’ve also written about figures like Yogi Wassan, another erstwhile laborer in the Pacific Northwest who would go on to become a traveling yogi and mystic who would be the center of a remarkable political intrigue in Oklahoma. In other words, the “bizarre, fantastic, and incorrect ideas about India” that you reference are not only important because they help us understand how people from India were viewed at the time, but also because they shaped how Indians saw themselves. In the same way that Thind’s citizenship claims must be understood in the context of early anthropological and philological theories propagated by the British Orientalists of the Asiatic Society and Indologists like Max Muller, his transformation into a traveling mystic drew on popular American views of the “Hindoo”. Would you agree with this statement? Relatedly, could you elaborate on this aspect of the aftermath of the Thind decision? It’s really a remarkable period.

PD: One of the many reasons that the 1923 Thind decision is so interesting is that it highlights the long-standing confusion Americans had placing South Asians into pre-existing racial categories. For nativists on the West Coast at the turn-of-the-century, South Asian immigrants were thought of like earlier waves of immigrants from China and Japan, another group of unskilled laborers that threatened to undercut wages. In much of the South, dark skin was enough to convince some Americans that South Asians should be considered Black, while not much more than a turban and robes was enough to convince others that a Black man was from India. As so often happens, perceptions of South Asians in the United States and ideas about their racial classification were shaped by other factors such as economic class, education, language, and religion.

Thind argued for his inclusion in the category of “White” on the grounds of caste, geography, and the racial science of his time. The accepted understanding of Thind, and one based on the brief decision, was that the Supreme Court denied Thind’s claim to being White because he did not fit in with the common understanding of what White was by the American public. I have argued that the decision might have hinged on Thind’s turban, given Justice Sutherland’s focus on how race could be determined visually and how other immigrants lost the outward signs of their cultures within a generation or two.

The Thind decision made South Asians “ineligible for American citizenship” and brought them under pre-existing laws that prohibited things such as land ownership and marrying citizens. The government also swiftly enacted a wave of denaturalization proceedings and took American citizenship away from about seventy South Asian Americans. Since they had already renounced their loyalty to Britain, that left them stateless, citizens of no country at all.

What Thind and many others like him found was that much of the American public (particularly metaphysical seekers) assumed that they were mystics, spiritual teachers, or had magical powers. There are humorous and ridiculous scenes in memoirs of South Asian immigrants during this time where they are taken for granted to be a meditation teacher or hired to serve as an exotic prop for a Spiritualist seance. For dozens of travelling yoga teachers and metaphysical lecturers, these stereotypes worked to give them instant credibility and recognition. From early display advertisements in newspapers, we know that simply advertising yourself as a “Hindoo Yogi” was enough to draw a crowd. So many of those same “bizarre, fantastic, and incorrect ideas about India” that rendered South Asian Americans as different and unassimilable, also provided the foundation for these new careers. So, while Orientalist stereotypes existed and were certainly harmful and limiting, it didn’t mean that they couldn’t also be used by the same people they were projected onto.

HH: I was hoping we could turn back to yoga specifically since that’s a focus of your research. This is obviously contentious topic today, with on-going debates about western yoga culture, and the extent to which it is culturally appropriative. Another debate is the extent to which contemporary yoga obscures the spiritual or religious roots of the practice. Could you give us a brief description of what the average American would have understood “yoga” to mean during this early period?

PD: Yoga as we know it today is largely a product of what is known as the hatha yoga revival in turn-of-the-century India, where yogic practices were combined with Western bodybuilding, Swedish gymnastics, and medical science, among other things. The fruits of the hatha renaissance only took hold in the United States around the time of the Second World War. Before then, ideas of what yoga was were, pardon the pun, flexible. Yoga was a matter of mental concentration or hypnotic power. Yogis were people with psychic abilities or those who could communicate with the dead. Yoga was a matter of breath exercises or dietary reform. Significantly, there were not only a range of ideas about what yoga was, all these ideas co-existed. No one concept of yoga in America was dominant.

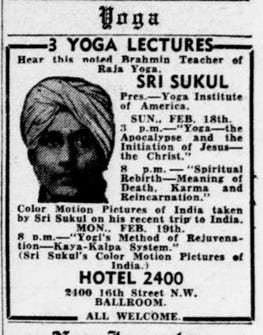

I think this is an important element that allowed dozens of South Asian Americans to travel around the Twenties and Thirties and make a living as yoga teachers. Definitions of yoga were varied enough that many people could pull from their different backgrounds and successfully appeal to the American public as yoga teachers. Those with an educated or literary background could rely on their ability to lecture and write. Others who had a background in wrestling and sports could offer calisthenics and teachings on health. My favorite example is Deva Ram Sukul, who parleyed his background in sales and advertising into his repertoire as a yoga teacher.

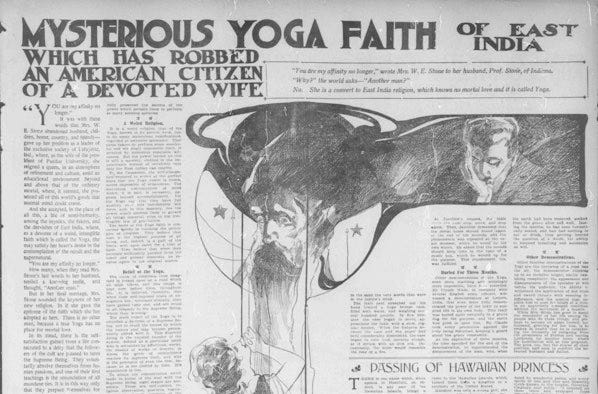

HH: The flexibility you reference certainly comes through in the media I’ve seen, and it goes both ways. In the same way that Yoga’s amorphous nature provided an opportunity for wandering Indians to make a living as teachers of “Yoga”, it also provided ample room for critics of Hindoo spirituality to attribute to yoga various social ills. One story that I found particularly interesting was the story of one Mrs. W.E. Stone, who was the wife of Winthrop Stone, the then president of Purdue University. According to contemporaneous newspaper clips, after Mrs. Stone attended a popular course at the university about “Yoga philosophy”, she felt sufficiently inspired to leave her husband and become a devout follower, which led her to Germany and then to an island in the South Pacific where she would join her fellow sun worshipers. Now it turns out that Mrs. Stone’s new religion was not related to yoga or Hinduism at all, but rather the “Order of the Sun”— a movement with origins in the German Lebensreform (Life Reform movement)— started by August Engelhardt, a German nudist who was convinced that humans should only consume coconuts. Nevertheless, in the extensive media coverage around her case, the blame is laid on the “Mysterious Yoga Faith” and “Indian philosophy” that was in vogue at the time. Indeed, “Yoga” is frequently targeted as a threat to women in particular. To give another quick example, in Mabel Potter Daggett’s 1911 essay, the “Heathen Invasion of America”, we are told that yoga “shattered the reason” of Mrs. Sara Bull, the widow of celebrated Norwegian violinist Ole Bull and a devotee of Vedanta, whose story I covered in a recent post. But back to your response—I think I would remiss not to ask you to elaborate. Can you tell us more about Deva Ram Sukul? What was his story?

PD: You bring up a great point. Yoga was popular among some people in the early-twentieth century, but it was also unpopular with many others. Yoga was considered strange and dangerous, and it was not uncommon for travelling yoga teachers to be mocked, harassed and even arrested. I’ve written about how an association of yoga helped to topple the Oklahoma state government in 1927 and how Bhagat Singh Thind was put in jail in Omaha in 1942. The nativist fears of migration from South Asia and the popular fears about yoga were not mutually exclusive. Polemics in the press often framed the presence of yoga teachers as a menacing foreign invasion and attacks on immigration often framed the imagined unassailability of “Hindoos” in religious terms and described them as naturally nihilistic and ascetic, or as a “dark, mystic race.”

As for Deva Ram Sukul, he came to the United States from British Guiana in 1916 as an agent for an Indian tea company, promoting the product at small gatherings of society women, retail stores, and larger events. He positioned himself as an authority on advertising and commercial trade with India, but after the changes in citizenship eligibility in 1923, he remade himself into a metaphysical lecturer and yoga teacher. Although much of what he taught was like his peers in America- lectures, private classes with instructions on breathing and visualization, and claims that he could communicate with spirit guides- he continued to engage with much of the same boosterism that he did as a tea salesman and used glass lantern slides and motion pictures to show his audiences glimpses of India. Sukul worked as a travelling yoga teacher for over forty years and died only weeks before the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that abolished the racial barriers to citizenship that were the catalyst to that career.

HH: Thanks so much for doing this, Philip. Before we go, can you tell us what you’re working on now?

PD: I am currently working on a podcast about the life of Rishi Singh Grewal, who was a Punjabi Sikh immigrant who could be considered one of the first people to teach yoga as we know it today in the United States. Grewal was also a vocal advocate for Indian independence and waged a lengthy legal battle to regain his citizenship after the 1923 Thind decision. The podcast will have interviews with experts and members of Rishi’s family and also contain a lot of surprises about his remarkable life.

An eye opening conversation! What Hinus were considerd just 150 yrs ago and today the world celebrated International Yoga Day! Proud to be Indian snd a devout Hindu.