The Ambivalent Role of Women in the Yoga Scares of Early 20th Century America

I had the fortune of coming across a 2015 essay by Philipp Deslippe, a doctoral student studying the history of American religion at UC Santa Barbara, about the “American Yoga Scare of 1927.” The “Yoga Scare” in question here involves Henry Simpson Johnston, a lawyer who won the governorship of Oklahoma in 1926, his secretary and confidante Mrs. Oliver “Mamie” Hammonds, and Hammond’s uncle, Judge James Armstrong. Deslippe elaborates:

The governor, his secretary and her uncle shared a bond beyond politics. All three of them deeply held their own personal array of esoteric and occult beliefs. Johnston was a serial joiner of fraternal organizations and was a member of the Klu Klux Klan, the Freemasons, and the Rosicrucians, and by his own admission counted Theosophy, New Thought, Unity, and Christian Science among his philosophical affinities. Mamie Hammonds was part of the Kamelia, a women’s adjunct to the Klan, and adhered to other groups by osmosis, through her husband the Freemason and her uncle Armstrong who was a Rosicrucian. Johnston, Hammonds and Armstrong also had shared interests in numerology and astrology.

In the summer of 1927 word began to spread about the eclectic beliefs of Governor Johnston and the two members of his inner circle. Hammond’s influence on Johnston was increasingly thought of as the result of hypnotism or some imagined occult power. One paper reported a rumor that Hammonds could send her spirit out through the keyhole of her office door to spy on political opponents. It did not help that Johnston, open about his beliefs in astrology, said that he would sign a bill during a one-hour period in the middle of the night because the zodiac would be more favorable. In September, Aldrich Blake, the secretary of a former Oklahoma governor, wrote a scathing, rumor-filled article for The Nation titled “Oklahoma Goes Rosicrucian.” The piece warned readers that Oklahoma was under a “dictatorship of the spirits,” and the charge that “Strange Gods Rule Oklahoma” was soon reported by newspapers as far away as Florida and Wisconsin.

Deslippe also notes another connection that drew suspicion: the Governor’s relationship with one Wassan Singh.

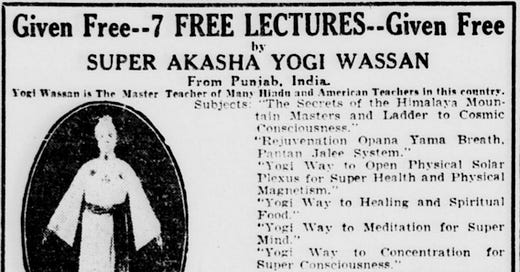

One of the most problematic of these associations was Judge Armstrong’s relationship with a Punjabi Sikh immigrant from the village of Ball named Wassan Singh. Wassan Singh came to the United States in 1906 and worked in the lumber mills of the Pacific Northwest for about a decade and a half until he reinvented himself as Yogi Wassan and began to travel and lecture as “Super Akasha” and “Hindu Hatha Yogi.”

While much of Yogi Wassan’s repertoire was similar to his peers, he placed a strong emphasis on physical wellness through diet, exercise, and breathing regimens. In his public lectures, Yogi Wassan would often perform feats of strength on stage and use his own brawny body as proof of his techniques.

Yogi Wassan arrived in Oklahoma City in late-November of 1926, three weeks after the elections that won Henry Johnston the governor’s office. He gave public lectures at the Sorosis social club for women, the New Thought-inspired Unity church, and in the banquet hall of Claussen’s Dinner Bell Cafeteria. As was standard, the free public lectures lead into series of private courses for paying students and individual consultations with the yogi. One of these students was Judge James Armstrong, who claimed to have received great health benefits from practicing the yogic breathing techniques taught by Yogi Wassan.

While breathing exercises may seem harmless today, as wave after wave of scandal hit the Johnston administration, the bonds between Armstrong and Yogi Wassan— both real and imagined— were the most damning. Armstrong not only appeared to be bizarre and foolish to the public, but the relationship even questioned where he placed his loyalty. The article in The Nation declared Armstrong’s yoga teacher to be “a sort of mystic pope of the quiet sect of Yogi” who despite advertising in newspapers, “slipped into Oklahoma in all his oriental grandeur.”

It’s a great story, so I was a bit surprised at the paucity of material I was able to find in the LOC archive:

Here’s an ad for Yogi Wassan published in the Evening Star in 1927:

And regarding Mamie Hammonds, most of the reports I was able to find were silent on her “Hindoo” ties, with one notable exception: The Daily Worker (yes, the mouthpiece of the American Communist Party)!

In this 1927 article she is referred to as the “Female Rasputin” and as “an adapt and believer in Yogi magic.”

The scandal around Governor Johnston’s ties to this “Female Rasputin” is a good illustration of the ambivalent role of women in the “yoga scare” narrative that prevailed in the early 20th century. On the one hand, women are often portrayed as victims of unscrupulous “hindoo mystics” who use their powers of hypnosis to lure them away from their families and religion. On the other hand— as is the case here— women become the antagonists themselves, using their newfound yogic powers to further nefarious occult agendas (Madame Blavatsky of Theosophical Society is the paradigmatic example here).

Consider the beginning of Mabel Potter Daggett’s “Heathen Invasion of America,” where the American woman is portrayed as an Eve figure enticed by the yogic snake to eat the forbidden apple of “knowledge of the occult”:

The story of W.E. Stone is a good example, and it appears to have received far more coverage nationally judging by the number of clips I’ve seen. The clip below is from the Washington Times, 1908, with the headline “Mysterious Yoga Faith of East India Which Has Robbed an American Citizen of a Devoted Wife”:

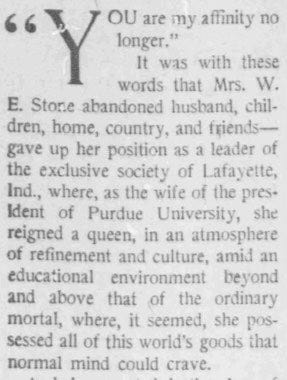

We’re told that W.E. Stone— the wife of Winthrop Stone, the then-president of Purdue University—“abandoned husband, children, home, country, and friends—gave up her position as a leader of the exclusive society of LaFayette, Ind., where as the wife of the President of Purdue University, she reigned as a queen, in an atmosphere of refinement and culture…she possessed all of the world’s goods that normal minds could crave.” She gave this all up for a life of “semi-barbarity, among the mystics, the fakers, and the dervishes of East India, where, as a devotee of a weird, intangible faith which is called the Yoga, she may satisfy her heart’s desire in the contemplation of the occult and the supernatural.”

Additional detail from another account published in the Charlevoix County Herald in 1911:

Having attended a popular course at the university about “Yoga philosophy, Mrs. W.E. Stone felt sufficiently inspired to leave her husband and become a devout follower, which led her to Germany and then to an island in the South Pacific where she would join her fellow sun worshipers. Now it turns out that W.E. Stone’s new religion was not related yoga or hinduism at all, but rather the “Order of the Sun”— a movement with origins in the German Lebensreform (Life Reform movement)— started by August Engelhardt, a German nudist who was convinced that humans should only consume coconuts. But that is beside the point. In this instance, we see how W.E. Stone is but a victim; notice how in both of the headlines above, it is the “Mysterious Yoga Faith” and “Indian philosophy” respectively that are blamed for her actions.

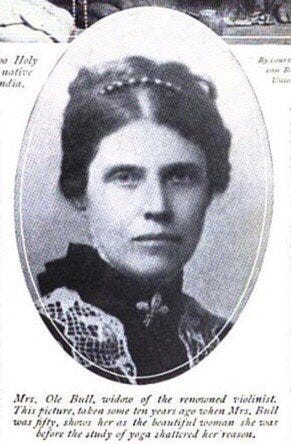

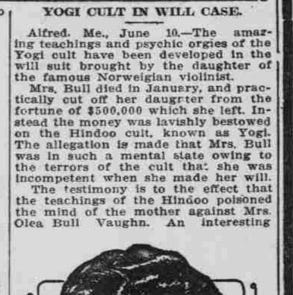

Another high profile case that deserves mention is that of Mrs. Sara Bull, the widow of celebrated Norwegian violinist Ole Bull and a devotee of Vedanta. Mrs. Bull was a prominent figure in New England intellectual circles, often hosting salons at her Cambridge, Mass apartment attended by academic luminaries including William James and Harvard Sanskritist Charles Lanman. Swami Vivekananda himself attended one of these salons and discussed Vedanta with Mrs. Bull and her guests. After her death in 1911, it came to light that Mrs. Bull had left the bulk of her estate to the Vedanta Society, a decision that was challenged by her daughter on the grounds that Mrs. Bull was mentally incompetent when she signed the will. In his essay “Hinduphobia and Hinduphilia in U.S. Culture,” Stephen Prothero notes that in the trial that ensued, “Hinduism was on trial too, since the main argument of Sherman Wipple, the daughter’s attorney, was that Hindus had driven Mrs. Bull insane” (Prothero 13).

The trial made headlines across the country, and it predictably featured prominently in Mabel Potter Daggett’s “Heathen Invasion of America”:

Daggett’s assertion that “yoga shattered her reason” in the caption above is consistent with the public narrative around the trial. Prothero recounts that the main argument was that the “Hindus had driven Mrs. Bull mad— or, as her petition put it, that the testator’s brain had been ‘inoculated with the bacteria of faith taught by Indian swamis” (Prothero 14). Similarly, in a contemporaneous account of the trial published in the Topeka Daily State Journal, we’re told that the main thrust of the testimony is that “the teachings of the Hindoo poisoned the mind of the mother against Mrs. Olea Bull Vaughn.”

Deslippe’s account of Governor Johnston’s impeachment is a fascinating read and a testament to how pervasive the suspicion of the “Hindoo” was at this time in American history. Whatever the underlying political motivations, the fact that Johnston’s opponents honed in on his association with Hammonds and Wassan Singh as a vulnerability reflects a judgment that these accusations would resonate with the public at large. And they were right, for the Governor was eventually removed from office. Deslippe echoes this point in his essay when he reflects on the “message” we can take from the impeachment:

It would be short-sighted, however, to think of Johnston’s impeachment as just a matter of vicious politics. More than anything else, there was an acute focus on the “Oriental” elements that surrounded the governor and his inner circle, even from those who recognized the entire impeachment as a farce. The media speculated endlessly on rumors of chanting, incense smoke, swamis, and yogis, and it is difficult to not see those same rumors in the single vague charge that removed Johnston from office.

The same loss of reason and self-determination imagined in previous yoga scandals was applied to Johnson, Armstrong, and Hammonds. Not just mere eccentrics, they were imagined to be inept and helplessly following the commands of a mystic philosophy, Yogi Wassan, or the nebulous “Strange Gods” that “ruled Oklahoma.” Unlike earlier scandals which diagnosed yoga as the cause of someone’s downfall in hindsight, the connection to yoga was able to take an active role in the collapse of Johnston and his inner circle. Johnston‘s impeachment can be seen as perhaps the most significant of the scores of yoga-related scandals in the first decades of the twentieth century, one that effectively removed a sitting governor from office.