Tracing the history of how the “Hindoo” became conceivable in America requires an attention to what Dr. Altman calls the “genealogy” of the “Hindoo,” which he describes as the “powers, identities, forces, constraints, agents, and discourses that form a particular category.”

But what exactly are those “powers, identities, forces, constraints, agents, and discourses”? I’d group them into three main threads: The first is the commercial or economic thread (the paradigmatic example being the New England merchants of the East India Marine Society); the second is the religious or missionary thread; and the third is what I’d broadly call the philosophical thread, which was focused among New England Unitarians and ended up producing spiritual movements like Transcendentalism, Theosophy, and even American Vedanta. These are of course neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive, and as we proceed through the 19th and 20th centuries, we often see— in Dr. Altman’s terms— how the different threads “overlap, include, and exclude one another.”

Now, back to the topic at hand: In shaping the contours of the religious thread referenced above, few figures were more influential than Claudius Buchanan. Born near Glasgow in 1766, Buchanan was appointed as a chaplain with the East India Company and spent much of his working life in and around Calcutta spreading the gospel to the heathen Hindoos.

During this period the East India Company was not particularly keen on Christian evangelism in India. The EIC was a business and first and foremost interested in keeping goods and money flowing, which meant keeping religious tension to a minimum (this would change in the aftermath of the First War of Independence in 1857). The EIC regularly patronized local temples and won favor from native rulers by helping fund festivals, much to the chagrin of local missionaries. Buchanan understood that in order to break the reticence of the EIC, he had to launch a public information campaign to convince the average Christian in the west that the Hindoos needed saving.

Buchanan was by all accounts a true believer. In a 1809 sermon titled “The Star in the East,” Buchanan establishes Asia as the future of Christianity, drawing on the story of the wise men who were said to have visited Bethlehem to see the birth of Jesus, after seeing a “star in the East”:

Two years later in 1811, Buchanan released his seminal book “Christian Researches in Asia” which, Dr. Altman notes, gave “American evangelicals their first images of religions in India during the early nineteenth century.” Excerpts from the book were published extensively in both New England newspapers and missionary journals like The Panoplist, making mainstream Buchanan’s “descriptions of Juggernaut and its ‘sanguinary superstitions’” (Altman 33). After describing the horrors of the Juggernaut, Buchanan excoriates EIC officials for considering the Jagannath Temple and pilgrimage a legitimate source of revenue.

To say that Buchanan’s PR campaign succeeded would be an understatement. His colorful depiction of the Juggernaut would become the definitive image associated with Hindoo religious practice for the next century, if not longer. It’s worth quoting Dr. Altman at length here:

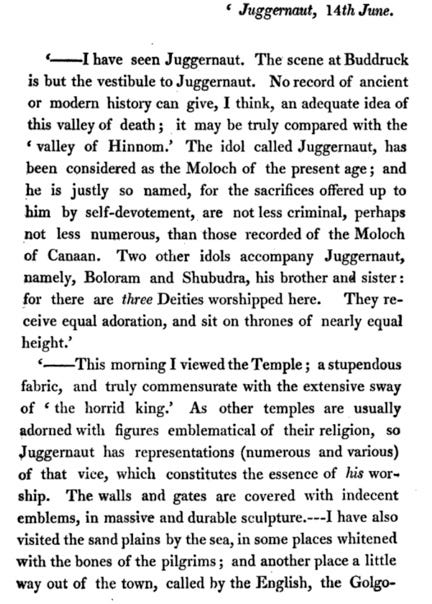

“Buchanan also described Juggernaut in biblical terms for his evangelical audience. Juggernaut was ‘the chief seat of Moloch in the whole earth,’ referencing the god whose worship was forbidden in Leviticus 18:21. Buchanan saw ‘the place of the skulls, called Golgatha,’ a reference to the place of Jesus’ crucifixion in the New Testament, ‘where the dogs and vultures are ever expecting’ the corpses of the devotees. The multitude worshipping Moloch-Juggernaut was ‘like that in the Revelations’ but, rather than Hosannas to Christ and his second coming, they yell in ‘applause at the view of the horrid shape and at the actions of the high-priest of infamy, who is mounted with it on the throne.’ The whole scene was ‘the valley of Hinnon,’ where children were sacrificed to the false gods in the Old Testament. This biblical description worked by inverting traditional Protestant tropes. Rather than the Golgatha where Jesus’ death atoned for sin, Juggernaut was a place of meaningless bloodshed. The worship was not the beautiful eschaton of the second coming, but ‘horrid.’ It was the valley of idolatrous blood shed to false gods, not the temple of worship to the one true God” (Altman 31).

In other words, in describing the Juggernaut, Buchanan made extensive use of Biblical reference and allegory as he knew that this would be effective in marshaling Christian support for evangelism in India. Buchanan records his observations of the Juggernaut in a series of journal entries reproduced in the text. I’ve included a sample below:

Buchanan’s tales of Hindoos throwing themselves underneath the wheels of the Juggernaut and women sacrificing their infants in an act of pagan blood-letting became deeply embedded in the American cultural imagination, to the point that the “Juggernaut” became something of a metaphor for everything that was unholy and cruel. By the late 19th century, the Juggernaut even appears in poetry! The following is excerpted from a poem authored by one Anne Marie Prescott as a part of a collection titled Makapala By the Sea, and subsequently reprinted in the Independent in 1899:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Buchanan’s account inspired not just disgust among American readers, but also fascination. In the coming years, a number of travel writers and missionaries would retrace Buchanan’s footsteps to see the infamous Juggernaut with their own eyes. What they found, however, was very different from what Buchanan described. There were no worshipers throwing themselves beneath the wheels of the car, nor were there piles of human skulls scattered among the temple grounds. Interestingly, the justification we often see for this inconsistency is not that Claudius Buchanan simply fabricated his account, but rather than the British authorities intervened to purge the festival of its most bloody elements. The following is excerpted from a first-hand account titled “Idols of the Hindoos” written in the early 20th century by one John J. Pool:

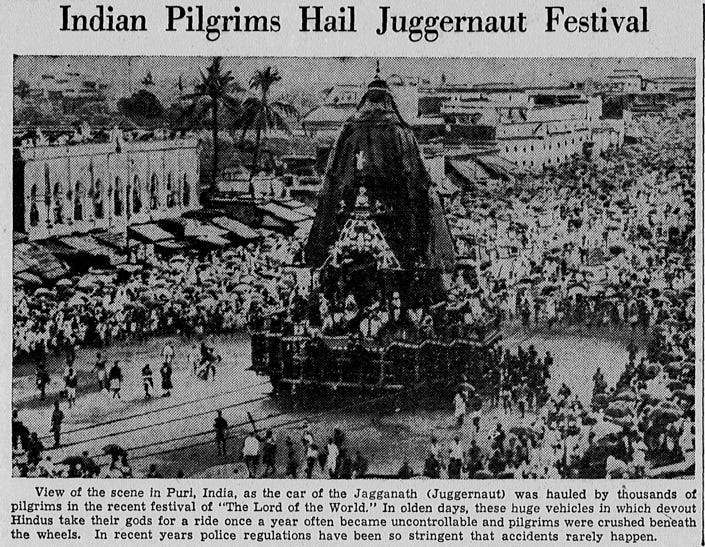

And here’s another, published in 1937:

In both of the accounts above, we see the the lack of violence attributed to British colonial intervention. Other writers simply refer to the earlier accounts as exaggerations: In a richly-illustrated feature titled “Most Cruel—Most Kind Idols in the World” published in 1912, the author— drawing on the research of an unnamed British archaeologist— claims that the “Juggernaut” — in contrast to the dreaded Kali— is in fact one of the “kindest” idols of the world and is entirely innocent of the sanguinary rites that had been attributed to him for so long:

The shifting narrative around the Juggernaut offers a valuable lesson in the study of #HindooHistory. Returning to our methodological diversion, the construct of the “Hindoo” was largely formed before the average American had ever met an actual Hindu. In this context a figure like Buchanan who was no doubt a vivid writer with a clear sense of purpose enjoyed an immense advantage in shaping early attitudes. However as the connections between India and America grew and the average reader gained access to more data, it became increasingly difficult to sustain the “Temple of Doom” narrative found in Buchanan’s writings. The way in which this narrative shifts (e.g. rationalizing the apparent fabrications in Buchanan’s account by crediting the British authorities) offers us an insight into how cultural attitudes evolve over time. This is a key theme in #HindooHistory and one we will surely explore in future posts.

This comment is coming from an Indian, through Christ’s teachings we know that

“God made us in His image and likeness” whereas, Hindu mythology (that’s why it’s called myths) made their god’s in the likeness of humans and in the likeness of animals and crawling creatures.

The elephant god, the monkey man, the snake god, god of birds, garuda, god of books, god of money, and so forth, (you may make up your own god), but I implore my readers to refrain from adoring any of these hindu gods because they were made by man.

Also, Not one of those gods can redeem you like the blood of Christ would, because only He atoned for our sins to the point of his death unlike any of these false gods and creatures.