"hindoo magic" in America

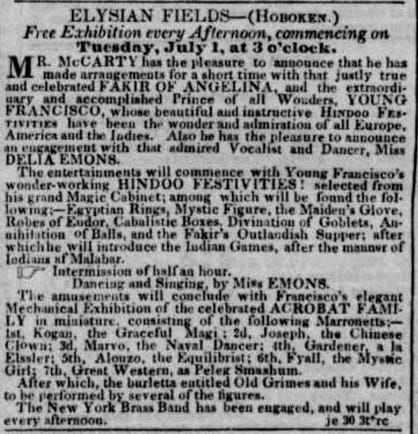

The first mention of a “Hindoo magic” I’ve come across is an ad published in the New York Herald on July 2, 1845, for an exhibit put on by a pair of performers known as the Fakir of Angelina and Young Francisco, in Hoboken, NJ:

We’re told that the “beautiful and instructive Hindoo Festivities have been the wonder and admiration of all Europe, America and the Indies,” and that “the entertainment will commence with Young Francisco’s wonder-working HINDOO FESTIVITIES: selected from his grand Magic Cabinet; among which will be found the following:— Egyptian Rings, Mystic Figure… and the Fakir’s Outlandish Supper; after which he will introduce the Indian games, after the manner of Indians of Malabar.”

It’s certainly an interesting combination of themes. Hindoo festivities featuring Egyptian rings and a Fakir’s supper. At first glance, the clip above reflects a fairly typical “Orientalist” view of the world, where the Hindoo, Egyptian, and Arab cultures all meld together into an exotic fantasy packaged for curious Americans. But as we proceed, we see that Hindoo magic in particular takes a life of its own. In 1860, we see an ad for the “The Eastern Renowned Fakir of Siva” who specializes in ventriloquism and “great feats” of magic like “Devil’s tea pot, Magic Mirror, Mystic Flower.”

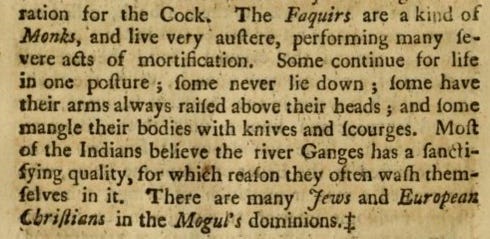

The figure of the “fakir” or “swami” was known to American audiences at an especially early date, as the traveling mendicant featured prominently in early missionary reports, and was subsequently discussed by Hannah Adams in the original edition of her Compendium on the Various Sects published in 1784:

The “Faquirs,” Adams tells us, “are a kind of Monks, and live very austere, performing many severe acts of mortification.” Some fakirs “continue to live in one posture, some never lie down, some have their arms raised above their heads, and some mangle their bodies with knives and scourges.”

We also have some evidence that the Hindoo was seen as particularly suited for magic. The clip below is from an article published in the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1890 about the theosophists:

“The Hindus, as a race, seem temperamentally better fitted than most other persons for the operation of natural magic, and many of their subjective hallucinations, as well as the objective phenomena they exhibit by psychologizing crowds, and thus inducing collective hallucinations, are certainly as wonderful as anything in ‘Arabian Nights.’ The true adepts not only believe, but know themselves to possess so-called supernatural powers, and the professional conjurers simply understand their own business.”

The passage above is consistent with what we see in missionary literature from this period. In a memoir about his time in India titled “Two Years in India, Or, Some Missionary Lessons, and how They Were Learned,” Nebraska missionary George Isham attributes the Hindoo resistance to conversion to a “mental perversion” that is endemic to paganism:

Paganism itself rendered the hindoo mind immune to reason and the logical faculty, while making it susceptible to magic and other “black arts.”

More broadly, magic played an important role as a foil to proper “religion” for scholars and theologians during this period. In the lead-up to the 1893 World Parliament on Religions, the organizers of the conference confronted the question of what exactly constituted “religion” worthy of being represented at the Parliament. While some argued that Christianity was the only true “religion” and the conference should therefore be limited to its various denominations, others took a more expansive view. Julia Ward Howe— a Unitarian, activist and author of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic”— defined religion as “aspiration, the pursuit of the divine in the human; the sacrifice of everything to duty for the sake of God and of humanity and of our own individual dignity” (Houghton 765). Howe then went on to distinguish magic from religion, claiming that “in some countries magic passes for religion, and that is one thing I wish, in view particularly of the ethnic faiths, could be made very prominent—that religion is not magic.” Altman elaborates that for Howe, magic “involved priests fooling people into thinking charms or rituals would bring them good luck, prosperity, or immortality” (Altman 127). Howe’s views on the distinction between magic and religion emerged from pre-existing notions regarding “priestcraft” popularized by the Deists. For the English Deists, “people were naturally drawn to a rational belief in a monotheistic god…but priests interjected themselves as selfish intermediaries that instituted heathen rituals, deities, and institutions that deceived the people” (Altman 14). This generalized theory would find its particular application to the Hindoo in Hannah Adams’s Compendium, where she described what Altman refers to as the “declension theory” of Hinduism, which held that the Hindu priestly class was responsible for corrupting the primitive monotheism of the Vedas via irrational superstition and idolatry.

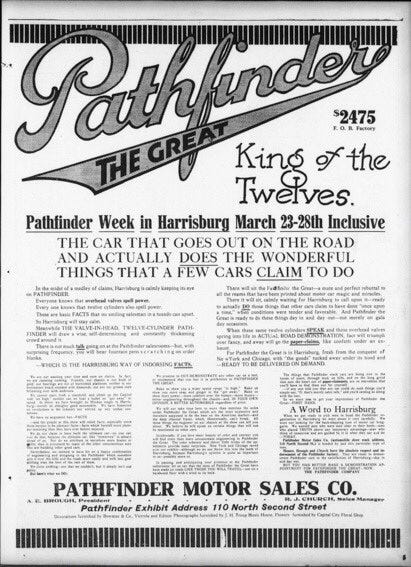

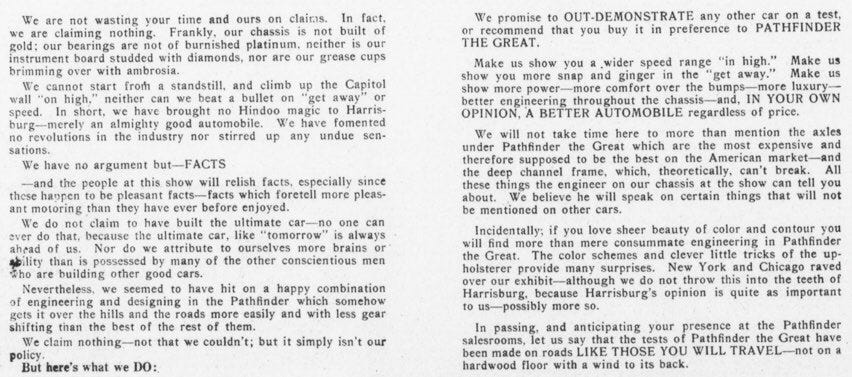

When merged with tales of mysterious Fakirs engaging in acts of yogic self-mortification, the resulting conglomeration proved a potent mix. Newspapers from the 19th and early 20th centuries are replete with ads featuring “hindoo magicians” and “hindoo magic,” and not just in reference to exhibitions: Hindoo magic became such a mainstay of the cultural vocabulary that it even make its way into advertisements for car dealerships! The ad for a local car dealership below was published in the Harrisburg Telegraph in 1916:

The ad reads: “We cannot steer from a standstill, and climb up the Capitol Wall ‘on high,’ neither can we beat a bullet on ‘get away’ or speed. In short we have brought no Hindoo magic to Harrisburg— merely an almighty good automobile”

Nor was “hindoo” magic a fringe phenomena in the entertainment world. The ad below is for one Howard Thurston— widely considered to be one of the greatest American magicians of all time and a rival to Houdini himself— for a performance at the Apollo Theater:

The appeal of the hindoo magician was such that performers who identified as such and performed mainstays such as the “mango tree trick,” the “rope trick,” or the “basket trick” achieved particular notoriety in an evidently crowded marketplace of “oriental” themed magicians traveling the country. In a particularly amusing clip published in the Los Angeles Herald in 1910, we see a bitter Ramses the Magician (the stage name for Polish magician Albert Marchinsky) take the Hindoo magicians to task, branding their mysticism as “fakery”:

When asked about the “celebrated Fakers of India” Ramses responds with the following:

The reference to “Fakers”— which emerged as a popular rendition of “Fakir” in American newspapers— points to a notable dynamic that emerged during this period. While Hindoo magicians regaled audiences with tricks and displays of hypnosis, spiritual figures from India were simultaneously drawing audiences into lecture halls and newly-built temples spreading the gospel of Vedanta and Hindu spirituality.

The reaction to the sudden growth in interest in Hindu spirituality (especially among wealthy urbanite women) was swift. The Hindoo “fakir” went from being a figure of fun who entertained audiences on stage to a villain, conniving innocent Americans out of their money and their wits. As part of a broader effort to delegitimize Hindu spiritual figures gaining a foothold in America, we see during this period a number of articles debunking hindoo magic. Here’s one published in the San Francisco Call in 1909:

“Mysteries of Hindu magic, of those bewildering and impressive feats which hold the attention of the beholder in thrall, are revealed as common trickery in a remarkable brochure by Mr. Hereward Carrington, which has just been published in London in the Annals of Psychic Research. Travelers from time immemorial have told tales of the performances of the fakirs which baffled the oriental mind and left the impression that they were genuine supernatural manifestations which could not be explained in the light of the knowledge of the western world. All these ideas, or most of them, at least, are sent glimmering by the expose of the methods of the supposed thaumaturgists of the orient, most of whose achievements are now proved to be merely the trickery of adept charlatans”

These same criticisms were then wielded against Hindu spiritual figures. The article below is typical, published in Brattleboro Daily Reformer in 1913:

Another example, this one published in the Tacoma Times in 1912:

In both instances, Hindu spiritual figures are conflated with trickster magicians whose preoccupation is not the spiritual edification of their followers, but rather economic gain.

The proliferation of hindoo magicians in the 19th century in an act of capitalist fervor was a quintessentially American response to the sudden influx of Hindu spiritual and cultural knowledge in America. While the missionary reports written by Buchanan and his ilk certainly inspired fear and revulsion, they also inspired fascination, and enterprising entertainers answered the call. The shift in public attitude towards the hindoo magician in light of the burgeoning success of Vedanta in the early 20th century is an illuminating example of how different streams of reception (in this case, the elite reception of Vedanta as a spiritual pursuit and the more “popular” stream of entertainment in the form of hindoo magic) entwine.

__________________________________________________________________________

Houghton, Neely’s History of the Parliament of Religions and Religious Congresses at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Michael Altman, Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Hannah Adams, An Alphabetical Compendium of the Various Sects Which Have Appeared in the World from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Present Day.

George Isham. Two Years in India, Or, Some Missionary Lessons, and how They Were Learned. (Madison: the University of Wisconsin - Madison, 1893).