In a letter written to Thomas Jefferson in 1814, John Adams— expressing his fear of the effects of factionalized electioneering on American political institutions— writes “Election is the grand Brama, the immortal Lama, I had almost Said, the Jaggernaught, for Wives are almost ready to burn upon the Pile and Children to be thrown under the Wheel.” Adams then elaborates the reference:

You will perceive, by these figures that I have been looking into Oriental History and Hindoo religion. I have read Voyages and travels and every thing I could collect, and the last is Priestleys ‘Comparison of the Institutions of Moses, with those of the Hindoos and other ancient Nations,” a Work of great labour, and not less haste. I thank him for the labour, and forgive, though I lament the hurry. You would be fatigued to read, and I, just recruiting a little from a longer confinement and indisposition than I have had for 30 years, have not Strength to write many observations. But I have been disappointed in the principal Points of my Curiosity. I am disappointed, by finding that no just Comparison can be made, because the original Shasta, and the original Vedams are not obtained, or if obtained not yet translated into any European Language.

Keen followers of #HindooHistory will no doubt find the image familiar: in referencing widow burning and infant sacrifice in connection with the “Jaggernaught,” Adams was reciting well-established tropes about the Hindoo that had been circulating in American missionary journals and newspapers since the late 18th century, courtesy of our friend Claudius Buchanan. What follows, however, bears further examination. Adams shares that he has “been looking into Oriental History and Hindoo religion,” and makes specific reference to the “Comparison of the Institutions of Moses,” a 1799 book written by the chemist and amateur scholar of religion Joseph Priestley.

That the founding fathers were discussing the “Hindoo” in their personal correspondence is quite remarkable, and a testament to how Buchanan’s work not only suffused the imagination of the average American church-goer, but indeed that of the American political elite as well: Adams’s reference to the “Jaggernaught” is made knowingly, with the assumption that Jefferson would understand all that it entailed. More importantly, in this correspondence we also see the beginnings of the intellectual reception of Hindu religious texts, a process that began with the foundation of the Asiatic Society in Bengal under William Jones in 1784.

The Asiatic Society was formed under the auspices of the East India Company in order to better understand the culture and history of the natives of India, so that the EIC could govern more effectively. Indeed, its mission was championed by none other than Warren Hastings, then Governor General of Bengal. Bernard Cohn in his book Colonialism and Its Form of Knowledge emphasizes the utility of the Asiatic Society’s work to the EIC’s administrative machinery, noting that “the knowledge which this small group of British officials sought to control was to be the instrumentality through which they were to issue commands, and collect ever-increasing amounts of information. This information was needed to create or locate cheap and effective means to assess and collect taxes, and maintain law and order” (Cohn 21). Regardless of the intent, however, the fruits of the Asiatic Society’s labor were not confined to India; by the early 19th century, translations of the Bhagavad Gita and the Manusmriti had made their way to American shores.

The introduction of Hindu spiritual texts came at a critical time. Scholars like Hannah Adams and Joseph Priestley were American pioneers in the burgeoning field of comparative religion, a field that was inextricably linked with a particular notion of religion that emerged from the English enlightenment. In “Religion” and Religions in the English Enlightenment Peter Harrison observes that “following the Reformation, the fragmentation of Christendom led to a change from institutionally based understanding of exclusive salvation to a propositionally based understanding” (Harrison 67). It was no longer a matter of finding salvation through the Church, but rather achieving salvation through “true religion.” But how did one determine which religion was the One True Faith? It was from this milieu that the Deists (whose ranks included Thomas Jefferson) emerged, establishing an extensive epistemology of religion and a rationalist methodology for navigating differences between the innumerable Christian factions and denominations that emerged following the Reformation. Harrison puts it plainly: “It would be expected that ‘religion’ and the strategies for its elucidation would develop in tandem. For this reason ‘religion’ was constructed along essentially rationalist lines, for it was created in the image of the prevailing rationalist methods of investigation: ‘religion’ was cut to fit the new and much-vaunted scientific method” (Harrison 2).

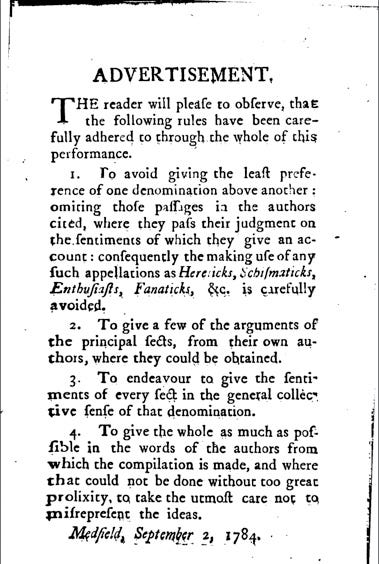

American scholars like Hannah Adams and Joseph Priestley were key figures in this Enlightenment project of systematizing religion. In the cover page to her 1784 book An Alphabetical Compendium of the Various Sects Which Have Appeared in the World from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Present Day (we’ll call it “Compendium” for short…), Adams describes her objective to fairly report the view of each of the denominations, so that the reader can rationally distinguish between them:

But how did the newfound Hindu spiritual texts fit into this system of religious thought? As noted above, the methodology that developed around this Enlightenment view of religion was designed to weigh the claims of competing Christian denominations: that Protestantism broadly construed represented the evolutionary zenith of “rational religion” was accepted as axiomatic. Although scholars of religion recognized that non-European peoples also had systems of religion, these were seen as “different manifestations of natural religion,” and were given a “a negative role in parochial conflicts within Christendom” (Harris 9). So as scholars like Adams and Priestley studied Hindu spiritual texts, the texts and the ideas they contained were “pressed into the service of the religious interests of the West” and “became heresies which were formally equivalent to some undesirable version of Christianity, be it papism, Calvinism, Arminianism, or any other of the myriads of Protestants sects” (Harris 9).

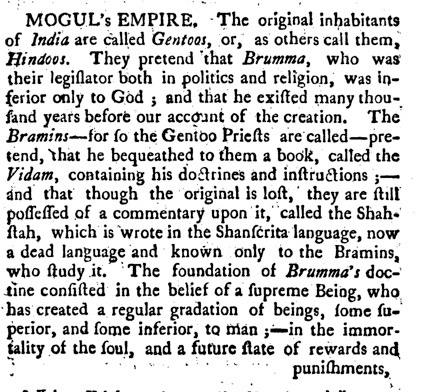

We can see this play out in Adams’s Compendium, which was originally published in 1784, with a number of updated editions subsequently released to reflect increased exposure to Hindu religious texts. In the first edition, the treatment of the Hindoo— or “Gentoo” as they were called at that time— was quite minimal, and included in a larger section about the Mogul Empire:

In the pages included above, we see what would become the “standard model” for the Hindoo in America. As Michael Altman notes, the analysis of the “Gentoo” religion is fit into a Protestant mold: Brahma is a Moses-like law-giver who revealed the Vedas to the Brahmin priests. Contained in these sacred scriptures are knowledge of the Supreme Being analogous to the Christian God. However this “primitive monotheism” once in the hands of the priests soon degraded into the religious of heathenry and idolatry depicted in Buchanan’s reports. Altman— who calls this the “declension theory”— describes it thusly:

Adams, via Guthrie, narrated the declension of Gentoo belief from the monotheism of the Veda to heathen idolatry. This decline occurred because of the superstitions of priestcraft. The brahmins led the people astray. In Adams’s telling, the brahmins failed to bring the “lower classes” up to their level by educating them with the proper beliefs, as a good New England minister did with his flock. Rather, the brahmins used idols to appeal to irrational senses instead of reason. Irrational idolatry displaced rational religion. Adams thus represented India as an upside-down place where religion declined away from truth instead of progressing toward it. This explanation of heathen religion through priestcraft and decline from a primitive monotheism was common throughout English thought, most notably in the theories of the English Deists. (12)

The “declension theory” allowed scholars like Adams and Priestley to simultaneously retrieve— and even admire— bits of theological and philosophical wisdom from the texts they had access to, while also reaffirming the popular depiction of the “Hindoo” as an idolatrous heathen that was popular in America at the time. Moreover, in placing the blame for this degradation on a corrupt priesthood, Adams recalled well-established criticisms of the Catholic clergy that animated the anti-clerical discourse popular among English Deists.

As Adams published subsequent editions of her Compendium, the treatment of the Gentoo (which now became “Hindoo”) expanded. In the edition of the Compendium published in 1801, Adams even introduced the figure of the “sanyassin” to American audiences, comparing the figure to the Christian conception of God (Altman 18). Adams also leveraged perceived similarities between Hindu and Biblical mythology as evidence for Christian truth. “Where the Bible and the ancient Indian texts agreed, they proved the universal truths of Christianity,” Altman notes, but “where the two systems departed, they testified to the uniqueness of the Christian revelation” (Altman 18). For all of Adams’s earnest intellectual curiosity, the Enlightenment project of religion was a fundamentally a Christian one, and as we proceed through our #HindooHistory journey, we’ll see how the contestation over the representation of the “Hindoo” becomes further entangled in American religious disputation.

____________________

Michael Altman, Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Peter Harrison, “Religion” and the Religions in the English Enlightenment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Two of the three things my American colleague said while discussing India-

1. ‘The ascetics- you know the ‘mind over matter’ folks who can keep their hands over their heads for hours.’ (Literally used the same words as Adam’s Compendium. The continuity of this hindoo imagination in the American mind is a lesson in narrative building. Thanks for taking the pains to study them.)

2. ‘The Dravidians had great culture and built great pyramids.’

Great and insightful piece. Thanks!