I’m proud to present a dialogue with Dr. Michael Altman, Professor of Religion at the University of Alabama. Dr. Altman received his PhD in American Religious Cultures from Emory University. His areas of interest are American religious history, colonialism, theory and method in the study of religion, and Asian religions in American culture. Trained in the field of American religious cultures, he is interested in the ways religion is constructed through difference, conflict, and contact. Dr. Altman is the author of Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu: American Representations of India, 1721-1893 (Oxford, 2017) and his most recent book, Hinduism in America: An Introduction, is out now. Enjoy!

HH: Dr. Altman, first of all, thank you so much for doing this. As readers of #HindooHistory know, your work has been instrumental to this project. I really didn't know what to do with all of these random newspaper clips that I was collecting until I fortuitously came across your first book, Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu: American Representations of India, 1721-1893. Your book gave me the intellectual scaffolding for the primary source material, so thank you for that! You can imagine how excited I was when I saw that you had written another book, Hinduism in America: An Introduction, which is the subject of our dialogue today.

To kick it off, in your introduction you note that you were hesitant to title the book Hinduism in America: An Introduction and would've preferred to call it Some Things Someone Somewhere Called 'Hinduism' in a Place Someone Somewhere Called America: An Introduction. I loved this, and I was reminded of your introduction to Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu, where you make a critical distinction: This is not about how "Hinduism" arrived in America, but rather about how it became conceivable in America. Can you elaborate on this methodological approach and explain how it informs your argument in Hinduism in America?

MA: Thanks so much, Vishal. I’m really glad you found my first book so helpful. You write these things and you never know who is going to read them or what they will do with it once they read it. Your work sharing the newspaper clippings you find is really important, and I really appreciate it. I’ve actually heard from other religious studies professors that they use your Instagram and my book together in their classes! So, thanks for the work you’ve done to bring public attention to this really interesting history.

The second book, Hinduism in America: An Introduction, was a really interesting opportunity to write a different kind of religious history. The book is part of a larger series of “<blank> in America” introductions and I wanted to write a book that could fit in that model but also raise some questions about the very idea of discrete unified traditions or religions (Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, etc. ) in America (or anywhere else for that matter). For me, the job of the religious studies scholar is not primarily to identify, describe, or define these traditions. Instead, our job is to pay attention to how individuals, communities, groups, institutions, nations, and other social formations define and identify these traditions. Put another way, many people who all call themselves “Hindu” or “Christian” or “Muslim” don’t all agree on exactly what it means to be “Hindu” or “Christian” or “Muslim,” and it’s not my job to solve that. It’s my job to pay attention to how and why people use those terms to describe themselves or others and what is at stake in those processes of labeling people and groups. As I tell my students, we are not umpires and we don’t call balls and strikes. We are play-by-play analysts who describe how the game is being played and analyze why it’s being played the way it is. My approach to the study of religion is that religion is one way people create “us and them” and my job is to figure out how and why that happens.

So for this book, rather than telling readers “this is what Hinduism is” and then “here’s where you can find it in America,” I wanted to walk through the ways the categories “Hindu” and “Hinduism” have been used by a variety of people, groups, communities, and institutions in America. I also wanted to introduce readers to some basic analytical terms in religious studies (difference, Orientalism, diaspora, etc.). So, each chapter looks at a set of examples of how and why people in America described or defined or identified “Hindus” or “Hinduism” and then uses those examples to illustrate one of these analytical terms. The chapters are loosely in chronological order but it’s not a single historical narrative. Rather, it’s a variety of examples of how somebody somewhere called something “Hindu.”

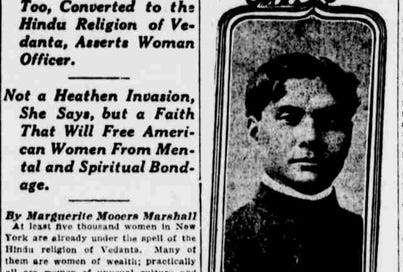

HH: That's incredibly gratifying to hear that Hindoo History has found its way into the classroom along with your book! I'm truly honored. And thank you for elaborating on your approach. In digging up these newspaper clips, I've found this idea of how these categories develop over time useful. In fact, you can really see how these different representations develop over time, sometimes in parallel, and other times clashing directly. For example, it's been edifying to see the stark contrast between the Hinduism of, say, New England socialites who really took to Vedanta after Swami Vivekananda's national tour, and that of the trenchant critics like Mabel Potter Daggett, who saw yoga and Vedanta as dangerous gateways to heathenry. One of the benefits of looking at newspapers is that you can see these fights taking place in real time. With that said, I was hoping you could help lay the intellectual groundwork and tell us how the story begins. In the first chapter, you observe that the earliest accounts from the early 18th century didn't even identify Indians as "hindoo," but rather as "heathens," which emerged as a sort of catch-all term for people who didn't actually have "religion" according to the prevailing definition among American Protestants at the time. Can you give us a quick primer on the intellectual and historical background for this binary categorization of the world? From where did this implicit theory of religion emerge?

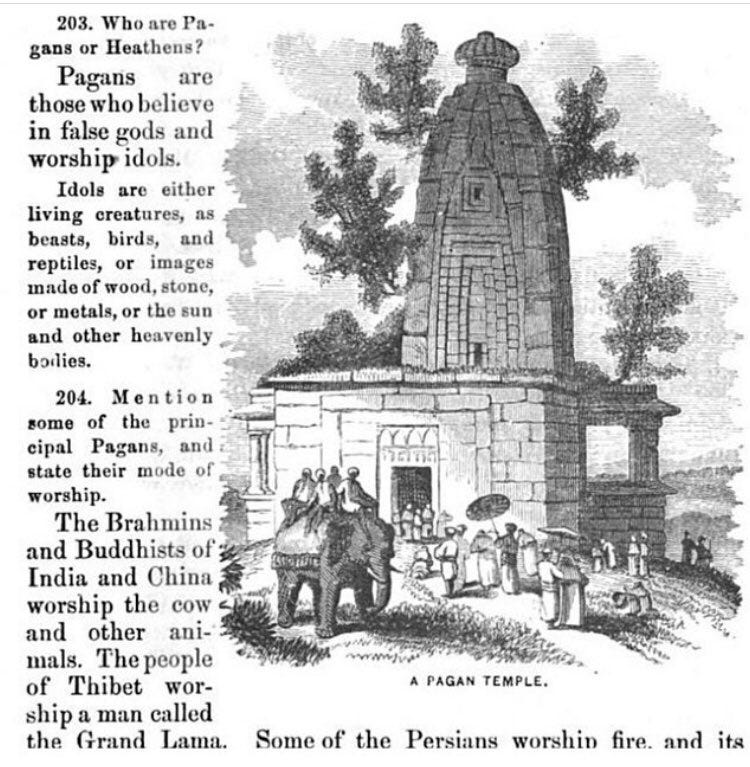

MA: I really like how you described that as an “implicit theory of religion,” because that’s exactly what it was. Not to try and go too far back, but two major European events totally changed how Europeans thought about religion: the Reformation and Global exploration. The Reformation fractured Western Christianity from one ostensibly unified Church to a variety of churches. Internally, Europe went from having religion to religions. Global exploration in the Americas, Africa, and Asia did the same thing on the outside. Europeans ran into all of these people doing things that looked like religion. Once again, it went from religion to religions. In order to make sense of this new plurality of “religions,” European thinkers developed a four-fold system for categorizing religions: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and heathenism. In their minds, there was Christianity (the only true religion), Judaism (the partial and preliminary forerunner of Christian truth), Islam (a false religion with a false prophet), and heathenism (everything else people are doing that looks like religion).

As Europeans, and later, Americans, gathered more information about these various “heathens” they began to differentiate things like “Hinduism” or “Buddhism” or even, “Lamaism.” This four-fold system began in the seventeenth century and lasted well into the early twentieth century, even as models with more “world religions” emerged in the nineteenth century. So, in 1893 there were 10 “world religions” according to the World Parliament of Religions (including Hinduism) but at the same time someone like Daggett is still operating within a model that includes “heathenism.” What’s important, though, is that nearly all of these systems of classifying “religions” maintained Christian supremacy in some form or another.

HH: Yes, this theme comes through very strongly in both Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu and Hinduism in America; the categorization of different world religions privileged Protestant Christianity as the evolutionary zenith of religious thought. As you note, this assumption informs the work of early scholars of comparative religion in America like Hannah Adams, in whose Compendium1 we first see what you call the "declension theory" of Hinduism. According to the declension theory, the Hindus once had something approximating the "true" religion of Protestant Christianity, but it degenerated over time, resulting in the bloody pagan rites described by the likes of Claudius Buchanan.2 Could you elaborate on this idea? What role did the arrival of translated Sanskrit texts like the Bhagavad Gita in the late 18th century play in the formulation of this theory? As a sort of addendum to this question, could you provide a quick primer on the transformations in the American religious landscape taking place at the time? How did domestic theological disputes inform these early treatments of Hinduism?

MA: That’s a lot of threads there in those questions! I think what ties them all together, though, is that there were real debates happening within Protestant Christianity in Europe and America. People were asking questions about the Bible and how it should be read and what it meant to be “divine revelation.” Many European and American Protestants used the Bible as the basis for human history and so they had to fit all these new religions they were “discovering” into that history. So, one way to do that was to go back to the Bible and find that the “religion of Noah” in the book of Genesis, the religion before the flood and even before the establishment of Israelite religion in the book of Exodus, must be a kind of original religion. Every step away from that, even the religion of the ancient Israelites, was a declension until that original divine religion was re-established through Jesus in Christianity.

At the same time, other ancient texts became a problem to be solved. For example, if the Vedas were older than the ancient Hebrew texts then does that mean that they actually contained the original pure religion? Did the Vedas pre-date Noah or Moses? That’s why someone like the Unitarian Joseph Priestley wrote his A Comparison of the Institutes of Moses with Those of the Hindoos in 1799. He wanted to compare the Hebrew texts to the Vedas and prove that the Vedas were derivative of the Hebrew texts. At the same time, other more religiously liberal Americans were reading the English translations of the Bhagavad Gita and other Sanskrit texts and finding them a helpful alternative or addendum to American Protestantism. What you get then, in the early 19th century is a split between conservative Protestants (especially missionaries) who see “Hindoos” and these Sanskrit texts as more and more “heathenism” and other more liberal groups like some Unitarians (not Priestley) and the Transcendentalists who read the Sanskrit texts approvingly.

HH: Your response hits on what I think is one of the most important threads in your work, namely an awareness of how domestic theological and socio-political developments in America shaped the representations of the "hindoo" in America. In Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu, you write "when Americans talked about religion in India, they were not really talking about religion in India. They were talking about themselves"-- this line really stuck with me. For example, the dueling representations of the “Hindoo” between conservative protestants and Unitarians takes place in the midst of two significant historical developments: First, during this period America saw the emergence of a revivalist Protestantism that emphasized conversion and evangelism, which in turn led to the widespread publishing and dissemination of missionary journals among American church-goers, and second, increasing Catholic immigration from Europe, which the Protestant establishment saw as a cultural and religious threat.

And as you argue quite persuasively in the book, this was a national conversation. The material even made its way into school textbooks! I wanted to quote the following passage from your book:

"Geography books presented American children with the variety of human difference around the world. Geography writers organized that difference through a set of hierarchical categories. They sorted the human world according to different levels of civilization, ranging from 'savages' to 'half-civilized' to 'enlightened.' Similarly, they sorted humans into racial categories such as 'Asiatic,' 'Malay,' 'European,' 'African,' and 'American' (as in Native America). Finally, they sorted out religious difference through four categories: Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and heathen. Each of these sets of categories was a hierarchy with enlightened European Christians at the top. As white Protestant children read about the various people in the world, schoolbooks reminded them that they sat atop these hierarchies of difference. The books allowed children to locate themselves and others and account for the difference between them. They also reinforced a child’s American identity as a Protestant Christian living in an enlightened democratic society and part of the white European race. In their sections on India, geography schoolbooks made sure to present readers with an account of Hindoo religion. The descriptions shared much in common with the missionary representations. 'Their religion is of the most degrading kind [it] even prompts widows to burn themselves on the funeral pile of their husbands,' read one geography book. Another one claimed 'the people worship images, and, under the blind influence of superstition, drown their children in the rivers.' The image of mothers drowning children in rivers such as the Ganges in order to please a god or idol was common in the schoolbook accounts of religion in India and must have been particularly powerful to child readers. Schoolbooks also took great interest in the caste system, which they presented as strict social and political hierarchy in stark contrast to American democracy and social mobility. These images of Hindoo religion as violent idolatry, sati, and caste fit within the categories of human difference that organized the schoolbooks. India was a half-civilized land of “Asiatic” heathens. According to the schoolbooks, it lacked everything America had: civilization, enlightenment democracy, European race, and Protestant Christianity. As American schoolchildren learned about Hindoo religion, the descriptions of violence and idolatry reinforced their identity as white Protestant, enlightened democratic Americans."

Could you elaborate on this idea of how portrayals of the "Hindoo" contributed to American identity formation during the 19th century? What was it about the "hindoo" in particular that made it suitable as a foil for the idealized American?

MA: Antebellum Americans were still trying to figure out exactly what it meant to be “American” and it was often easier to identify what wasn’t American than what was. Schoolbooks in particular played an important role in describing what it meant to be “American” because educational and political leaders saw the common public schools as vital to the fledgling American democracy. Schools had to teach children how to be good citizens and how to be good Americans so they were at the forefront of constructing what being “American” meant. The representations of “Hindoos” became really useful as a foil because India was far enough away to be “exotic” and strange, but close enough because of American trade relationships, missionary reports, and British Orientalist publications to be familiar. Catholicism was similarly both strange and familiar because it was Christian and European but decidedly “other” to Protestant Americans. So, while Catholic others arrived from Ireland, Germany, and France reports and images of “Hindoos” arrived at the same time. Both represented people tied up in “priestcraft,” “superstition,” and “idolatry.” Both provided a powerful other for the American Protestant establishment of educators, political leaders, and writers to use to represent what was and wasn’t “American.”

HH: The melding of prejudices you reference is of course best illustrated by the infamous "American River Ganges" comic published in Harper's Weekly in 1871, which you feature in both of your books. Followers of #HindooHistory will find the image familiar, but I'll go ahead and include it below for new readers. It's certainly striking. I’d like to press on this theme a bit, because it's so far reaching and hits at another key theme in your book: agency. In your second chapter on American Orientalism, you reference Edward Said’s third formulation of Orientalism, which is described as “a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority of the Orient,” by “making statements about it, authorizing view of it, describing it, by teaching it, settling it, ruling over it.” You build on this definition in your work by confronting the idea of not just what the "Hindoo" was to 19th century Americans, but who was speaking on their behalf. You write:

"The ways Transcendentalists, Theosophists, and Unitarians wrote about India did just that, representing India as a shadow or double of America. Even as Orientalist Americans praised India for its mysticism, they nevertheless found it wanting and still in need of the rationality, materiality, and industry of America. Using the mystic East to critique the materialist West was an act of power by Orientalist Americans that kept India subservient to American interest. Put another way, American Orientalism did not allow for India to exist in and for itself but rather saw India as a resource for the betterment of America."

In other words, whether it was hostile missionaries or Transcendentalists immersed in the Bhagavad Gita, all of them relied on representations of the "Hindoo" produced and disseminated by non-Indians, whether American missionaries or the Orientalists of the Asiatic Society3 in India. This was even true of early spiritual reformists from India, including Ram Mohan Roy and Swami Vivekananda. Can you elaborate on this dynamic a bit more? What united Indian reformers with thoroughly American figures like Emerson and Thoreau? Were they all Orientalists in their own way?

MA: Yes, the agency question is an important one. In the case of Ram Mohan Roy, it was his English publications arguing with the British Protestant missionaries that caught the attention of Unitarians in America. Roy had published a book of Jesus’s sayings that removed all the miracles from the New Testament and this infuriated the British missionaries stationed at Serampore, outside Calcutta. Roy even went so far as to argue that the missionaries’ idea of a trinitarian three-in-one God was no different from the variety of gods in Hindu religions. At the same time in New England, Unitarian Christians and “orthodox” trinitarian Protestants had their own arguments brewing about the nature of Jesus and the unity of God. So, as the back and forth between Roy and the missionaries made its way into British and American missionary journals, the similarity between Roy’s spat with the missionaries and the arguments in New England jumped out to the Unitarians. They began to champion Roy as a Unitarian Hindu or even a Unitarian Christian. So the only reason Roy showed up in American Unitarian publications was because he was a useful figure in their own fight with their Protestant neighbors. And it was Roy’s early English translations of Sanskrit texts that got picked up by Thoreau and Emerson.

Similarly, though decades later, Vivekananda found an audience in American among middle and upper class white Americans who wanted an alternative to the established American Protestantism. From his speech at the World’s Parliament of Religion forward, Vivekananda was very shrewd in his messaging. He used terms like “spirituality” and “science” to emphasize that the philosophy and yoga he taught was compatible with the liberal and metaphysical (as historian Catherine Albanese calls it) religious alternatives those Americans wanted. Both Roy and Vivekananda used the existing orientalist distinction between a “material” West and “spiritual” East to appeal to Americans disaffected with their religious options and looking for something more spiritual.

So, were they Orientalists in their own way? I don’t think so. Rather, they played by the rules that Orientalism had set for them so that they could find an audience and be heard. So, when we think of agency in these cases, I think it’s important to pay attention to the ways these Indian reformers chose to navigate the situations they found themselves in. Their agency—their choices—were limited (as all of ours are in some way) but what is interesting is what they did with those limited choices to find an audience in America.

HH: That's fascinating and it gives us a perfect segue into another topic you address in your book, the role of the diaspora. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries when many of the figures we've discussed were active, one constant is the lack of a significant Indian population in America. To the extent that the average American had any direct knowledge of an Indian or a "hindoo," it was through one of the many Itinerant Indians-- both Hindu spiritual figures and recent converts to Christianity-- who would travel throughout the country giving lectures. This of course changed in the late 20th century, when Indians started to immigrate to America in greater numbers. It is at this point that actual Hindus clashed with the representation of the "Hindoo" that preceded their arrival. In your book, you track this clash through a number of events, including the California textbook controversy in the early 2000s4 and, more recently, the "Dismantling Hindutva" conference. How do you understand these events in context of the historical representations of the "Hindoo"?

MA: For me, as an outsider who does not identify as Hindu, I put these events into the larger context of the ongoing discourse about what counts as “Hindu” or “Hinduism.” In both the California textbook case and the “Dismantling Hindutva” conference, individuals and groups were trying to define what was or wasn’t Hinduism. Similarly, Vivekananda, the traveling yogis of the early 20th century, Ralph Waldo Emerson, 19th century schoolbooks, and Joseph Priestley were also deploying definitions of what was or wasn’t Hinduism or Hindu or even Hindoo. The process of claiming authenticity and asserting a definition is the same. But across all of those examples, the stakes are different. That’s something I’m always trying to understand in my work and it’s something I press my students on: what are the stakes here? Who wins and loses? What do they win and lose? In those two more recent examples there are really important political stakes on both sides of the controversies. As a scholar of religion, I don’t see it as my job to pick a side or to tell anyone what Hinduism really is. I write about this in the introduction to Hinduism in America. I’m not going to tell anyone which definition is the real one. But I will try to explain what is at stake with any given definition and what the conflict is about. More broadly, my basic approach to the study of religion is that religion is a way people make “us” and “them.” For me, Hinduism in America is a fascinating example of the variety of ways people can make “us” and “them.”

HH: Thank you so much for doing this, Mike. It's been a pleasure discussing your book, and I hope we can do this again soon.

Hannah Adams was an 18th century scholar of comparative religion. Her book, An Alphabetical Compendium of the Various Sects Which Have Appeared in the World from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Present Day, is a key source for understanding early American attitudes towards the “Hindoo.” You can read more about her work in the post linked below:

Buchanan was born in Glasgow in 1766 and worked in and around Calcutta as a chaplain for the East India Company. He is famous for his account of the “Juggernaut.” You can read more about him in the post linked below:

The Asiatic Society was established in Bengal under the auspices of the East India Company. Through its translation of Sanskrit texts like Charles Wilkins’ Bhagavad Gita in 1795, the Asiatic Society played a key role in disseminating Hindu religious and philosophical texts in America.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_textbook_controversy_over_Hindu_history#:~:text=The%20Texas%2Dbased%20Vedic%20Foundation,textbook's%20portrayal%20of%20the%20caste