When Indians began arriving on the West Coast as migrant labor in the early 20th century, the opposition from the general public was immediate and pronounced. Politicians called for their expulsion.The Hindoo was referred to as the “scum of the Orient” and newspaper editorials across the country warned that the Hindoo’s unsanitary habits and their practice of caste would pose a threat to the health and safety of the American public and preclude assimilation. This “Hindoo peril” reached a crescendo in 1907 in Bellingham, WA, when a group of 500 white working men violently expelled Indian migrant workers from the city. The Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project provides a succinct summary of what transpired:

On September 4th, 1907 five hundred white working men in Bellingham, WA gathered to drive a community of South Asian migrant workers out of the city. With the mission of “scar[ing] them so badly that they will not crowd white labor out of the mills,” the growing mob rallied and went to work.1 The rioters moved through town, breaking windows, throwing rocks, indiscriminately beating people, overpowering a few police officers, and pulling men out of their workplaces and homes. They eventually rounded up two hundred or so of the South Asian immigrant workers in the basement of City Hall to stay the night. The mob was successful in that within ten days the entire South Asian population departed town. Despite promises of protections from city officials, the South Asian workers well understood that there was no protection for them in Bellingham and migrated up and down the Pacific coast looking for safer and saner living conditions.

How should we understand the Bellingham Riots today? Everyone agrees that the Indian laborers were identified as “Hindoo”, so should we see the riots as a historical example of “hinduphobia”? Or does the fact that the majority of the workers were actually Sikh mean this was actually an instance of anti-Sikh prejudice? Or maybe both of these explanations are overstated, and the riots can be better understood as a product of simmering economic resentment and nativism against newly arrived migrant workers who were— at least according to the perpetrators— driving down wages and pushing white American labor out of their jobs?

Dr. Audrey Truschke— an Assistant Professor of History at Rutgers University— recently proffered her own interpretation of the riots, presented in the short twitter thread below:

According to Dr. Truschke, “Hindoo” was simply an ethnic designator that was used to refer to Indians of all religions and so any assertion of what we would today consider “anti-Hindu” prejudice is ahistorical (and likely politically motivated). For Dr. Truschke, this is further supported by the fact that most of the victims in the riots were in fact Sikh or Muslim. How could the riots be an example of anti-Hindu prejudice if the victims weren’t even Hindu?

Does this argument stand up to scrutiny? Let’s start by examining Truschke’s assumption that “Hindoo” simply an ethnic identifier, the early 20th century equivalent of “South Asian”. Followers of #HindooHistory will not be surprised to learn that this is not consistent with the historical record. The figure of the “Hindoo” was situated in a broader system of religious categorization that emerged during the age of global exploration. As Dr. Altman observed in our recent interview, the Reformation fractured Christianity and in order to navigate the theological differences between the different denominations, “religion” emerged as an abstract category. The European encounter with the spiritual traditions of other cultures— traditions that “looked like religion”— birthed a four-fold system of categorization: Christianity, Judaism, Islam were all actual religions—with Protestant Christianity designated as the only “true” religion— and heathenism became a catch-all category for everything else that looked like religion, including the traditions of the “Hindoo”.

From the early 19th century when the figure of the “Hindoo” first makes an appearance in American missionary journals and newspapers, its representation is inextricably tied to missionary critiques of the native spiritual traditions of the Indian subcontinent, which we broadly refer to as “Hinduism” today. The first image of the “Hindoo” to penetrate the public consciousness was Anglican missionary Claudius Buchanan’s vivid and no doubt partially fabricated account of the “Juggernaut” in Puri, a bloody picture of barbaric pagan idolatry featuring fanatical worshipers throwing themselves under the wheels of the Juggernaut and women sacrificing their children. Buchanan made ample use of references to the Old Testament— even referring to the Juggernaut as the current day Moloch—to encourage readers to see the Christian mission in India in Biblical terms.

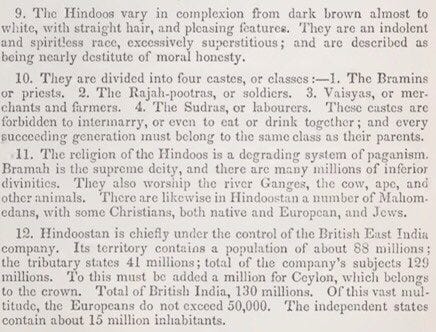

The “Hindoo” also served as a convenient foil for 19th century America. The work of Hannah Adams is instructive. Adams— an early scholar of comparative religion— saw the heathen idolatry of the Hindoo as a pagan degradation from the pristine monotheism of the Vedas. The purpose of this so-called “declension” theory was two-fold: First, it helped scholars reconcile the barbarity of the Hindoo as depicted in the writings of Claudius Buchanan and other missionaries with the sophisticated philosophical texts from India that were beginning to make their way to American shores via the Asiatic Society in Bengal; and second, the fate of the benighted Hindoo offered a cautionary tale for American readers, a grisly picture of what they could become if they strayed away from Protestantism. This wasn’t a message confined to scholarly works of comparative religion either; school textbooks during this period drew a stark contrast between American Protestantism and the pagan religion of the Hindoos in order to aid identity formation among American school children.

Dr. Altman explained this dynamic as follows in our recent interview:

Antebellum Americans were still trying to figure out exactly what it meant to be “American” and it was often easier to identify what wasn’t American than what was. Schoolbooks in particular played an important role in describing what it meant to be “American” because educational and political leaders saw the common public schools as vital to the fledgling American democracy. Schools had to teach children how to be good citizens and how to be good Americans so they were at the forefront of constructing what being “American” meant. The representations of “Hindoos” became really useful as a foil because India was far enough away to be “exotic” and strange, but close enough because of American trade relationships, missionary reports, and British Orientalist publications to be familiar. Catholicism was similarly both strange and familiar because it was Christian and European but decidedly “other” to Protestant Americans. So, while Catholic others arrived from Ireland, Germany, and France reports and images of “Hindoos” arrived at the same time. Both represented people tied up in “priestcraft,” “superstition,” and “idolatry.” Both provided a powerful other for the American Protestant establishment of educators, political leaders, and writers to use to represent what was and wasn’t “American.”

Which brings us back to the Bellingham Riots. Indian immigrants began arriving on the West Coast in the early 20th century amidst a perfect storm. Americans had spent decades reading stilted accounts of the Hindoo’s religious and cultural practices, in newspapers, textbooks, and missionary journals. In addition, in response to the Vedanta Society’s meteoric rise in popularity among the American elite following Swami Vivekananda’s speech at the World Parliament in 1893, we see a growing backlash against the Hindu spiritual practices like yoga and meditation in the early 20th century. From being a curiosity, yoga became— in Mabel Potter Daggett’s words— a gateway to Hindoo paganism and “the way that leads to domestic infelicity and insanity and death.”

While it is important that we acknowledge that the laborers were for the most part Sikh, we should avoid imposing our modern conception of religious identity anachronistically on to the past; religious identities at the time were far more fluid than they are today and the anti-Sikh prejudice of the broader public (e.g. contemporaneous newspaper accounts make frequent mention of the victims’ turbans and beards) would have existed seamlessly among a broader prejudice against the “hindoo”. As Dr. Altman observes, “to the white Americans looking for work and wages on the West Coast, these Sikh and Hindu immigrants were all ‘Hindoos’” and “in calling these South Asian immigrants ‘Hindoos,’ regardless of their religious self-identities, white Americans racialized religious difference…Religion and race co-constituted the ‘Hindoo other’ to white Americans on the West Coast” (Altman 147).

As Indian laborers increased in number, economic resentment from white workers seamlessly melded with preexisting racial and religious prejudice against the Hindoo. In trying to understand the Bellingham Riots today, it is critical to understand this broader social and cultural context. Dr. Truschke is correct that “Hindoo” was an ethnically elastic term, but by conveniently eliding how the Hindoo was represented in American media and culture for the decades preceding the riots, she ends up making the same error she attributes to her opponents: the elevation of contemporary political agendas over the historical record.

_________________________

Michael Altman, Hinduism in America (Oxford: Routledge, 2022).

Interesting read . thank you